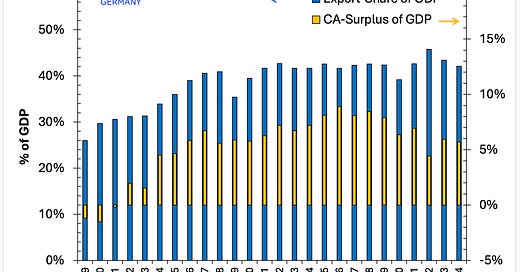

I've tried to create a bar chart showing Germany's export share and current account surplus as percentages of GDP from 2000 to 2024.

This visualisation makes it easier to directly compare the two metrics for each year.

Parallel Growth

The chart clearly shows how both metrics have generally increased over time:

Export share grew from 30% in 2000 to 47% in 2024.

Current account surplus increased from 0% in 2000 to 8% in 2024.

Proportional Changes

We can see that as exports increased, the current account surplus also increased, though not at the same rate. This indicates that while Germany exported more, its imports also grew, but not as rapidly as exports.

Temporary Fluctuations

Note the slight dip in both metrics around 2020 (supply-chain issue), likely reflecting global economic disruptions (COVID-Crisis) during that period, before recovering by 2024.

I tried a visualisation to illustrate the conceptual relationship among Germany's export share and current account (CA) surplus over time, showing how they have generally moved in parallel.

Bottomline:

Germany's CA-surplus is closely linked to its export performance. As exports increase relative to imports, the trade balance improves, contributing to a higher CA-surplus.

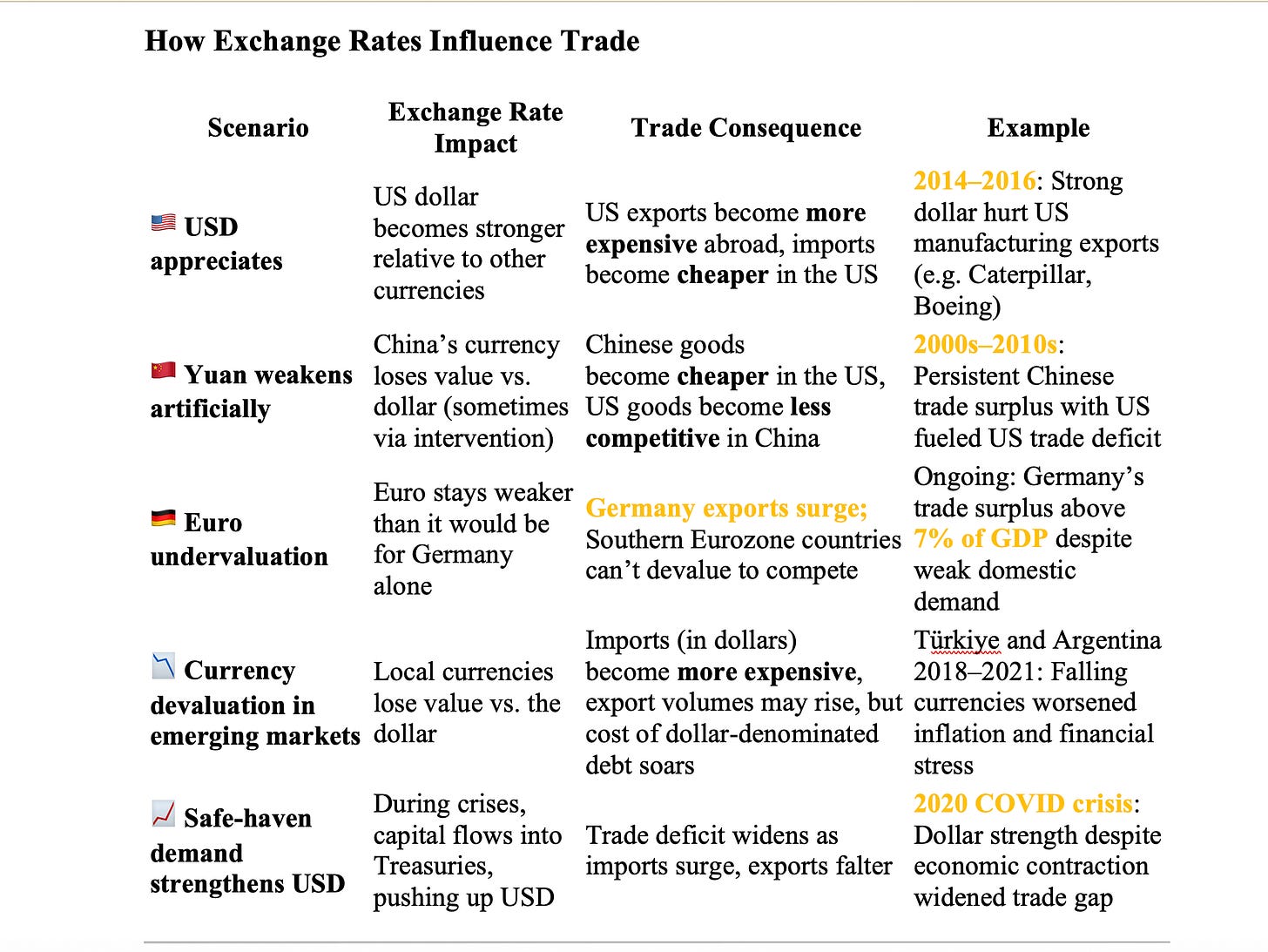

Explaining flows of goods with flows of capital simply does not work.

Exchange rates act as the “price tag” on a country’s goods and services globally. When capital inflows push up the currency, the trade balance often deteriorates, even if the economy looks strong. Exchange rates should reflect economic fundamentals, not speculative capital surges.

Obviously, the race for current account surpluses (unlike trade as a whole) is a zero-sum game for all countries in the world. Hence, some countries would have to abandon the idea of running current account surpluses (“mercantilist policies”).

Trade Deficits and Capital Flows

I can’t help but question the thesis that “US trade deficit is mainly reflected America’s attractiveness as place to invest”.

If every country tries to run a current account surplus, it becomes mathematically impossible. Global trade is not a game where all players can simultaneously "win" by accumulating surpluses.

Without further ado, policy coordination is needed to avoid a «beggar-thy-neighbor» world where every country tries to grow via net exports.

Note:

The neoclassical growth theory (mostly based on “Solow Model”) is misleading as it assumes that what is a necessary condition for investment for an individual household (micro level) - under particularly restrictive conditions - namely to save more, can also be extrapolated (as a sufficient condition) to investment by entire national economies (macro level).

Yet the fact is that a private household's attempt to save more, i.e. to spend less of its expected income, is a major obstacle to investment (“fallacy of composition”).

Savings ≠ Investment mechanically:

The neoclassical assumption that saving automatically funds investment via interest rate adjustments ignores the role of aggregate demand.

And this is not just a theoretical mistake - it has real policy consequences, especially when it leads to overemphasis on saving and under-appreciation of demand, finance, and distributional dynamics.