Trade Deficits and Capital Flows

What if all countries in the world started saving like Germany?

I can’t help but question the thesis that “US trade deficit is mainly reflected America’s attractiveness as place to invest”.

In other words, I think the idea that “trade imbalances are just the outcome of investment flows or benign market preferences” does not hold.

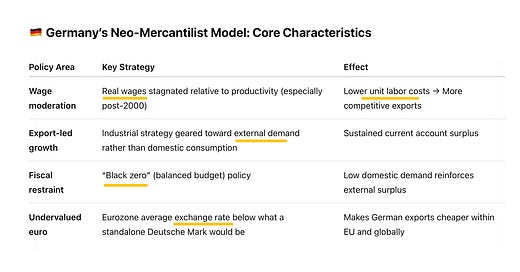

Instead, it shows, in my opinion, how policy choices, especially wage policy, can systematically shape competitiveness and trade balances.

If large capital inflows automatically caused trade deficits, then Germany, a top destination for global capital (e.g. German Bund investors, industrial M&A), should have a trade deficit - but it doesn’t.

Germany shows that structural policy decisions (like wage suppression) can drive competitiveness and surpluses, even without currency manipulation in the traditional sense.

It is an open secret that Germany actively engineered competitiveness through internal devaluation, not market magic.

Thus, the trade surplus wasn’t an accident - it was a national policy priority, with spillovers for its trading partners.

Germany runs a large current account surplus (6–8% of GDP), primarily from exports to the rest of the EU and beyond.

In a fixed currency zone like the Eurozone, other countries can't devalue their currencies to regain competitiveness.

This means Germany’s surpluses are mirrored by deficits elsewhere, particularly in Southern Europe (e.g., Greece, Portugal, Spain).

It is crucial to underline that post-2000, Germany practiced wage restraint, keeping labor costs low relative to productivity.

This made German goods cheaper, but also meant domestic demand lagged, pushing firms to rely more on exports.

Other EU countries that raised wages or had less fiscal discipline lost competitiveness within the Eurozone.

What role does the European Central Bank (ECB) play against this backdrop?

The ECB sets a single interest rate for all Eurozone members. But Germany’s low inflation and conservative fiscal stance exert downward pressure on ECB policy.

And this can result in policy misalignment - what’s right for Germany may be too tight for weaker economies with higher unemployment or slower growth.

In addition:

Germany’s trade surpluses were often recycled into loans to deficit countries, contributing to credit booms (e.g. Spain) before the 2008 crisis.

When the euro crisis hit, those countries had large external debts -financed by German capital.

This led to tensions and bailouts, with Germany insisting on austerity in return.

Bottomline:

Germany’s neo-mercantilism challenges the idea that trade deficits are just a side effect of being “popular.”

It shows that trade balances can be (and often are) shaped by deliberate policy, especially through wage and fiscal restraint - not just capital flows.

Germany’s success story has come at a cost to EU cohesion. In a shared currency area, national economic policy has continental consequences.

What would happen if all countries in the world, like Germany tried to start saving more than is necessary for themselves?

Obviously they can't because the world as a whole does not have a current account balance. Hence, saving cannot explain a country's current account surplus.

Without coordinated reforms (e.g. wage policies, fiscal flexibility, etc.), internal imbalances may continue to strain the European project.