Why the Demand vs. Supply Framing Matters

US Labor Market with a declining break-even job growth

Bank of America Research economists note that the Fed will not cut interest rates in 2025, despite a recent wave of disappointing jobs data.

The reason: The U.S. economy is headed toward a battle with stagflation - not recession - and cutting rates could worsen that toxic mix of stagnation and inflation.

There are two major factors, according to the new research: 1) tough new immigration restrictions and 2) a fresh series of import tariffs.

The key distinction comes down to labor supply, not just demand.

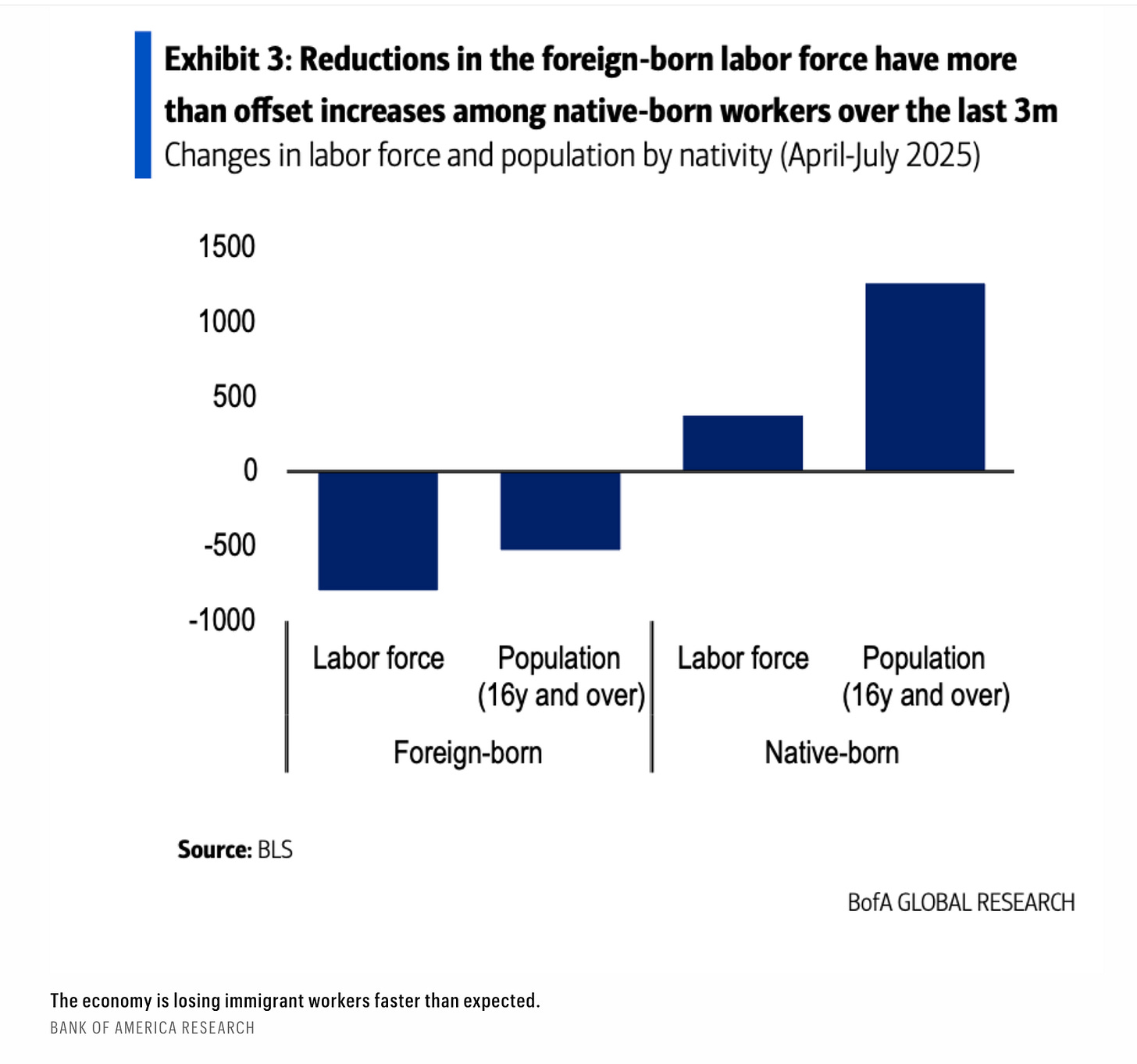

The BofA research points to a sharp contraction in the foreign-born labor force, down by 802,000 since April, as immigration policy has tightened dramatically.

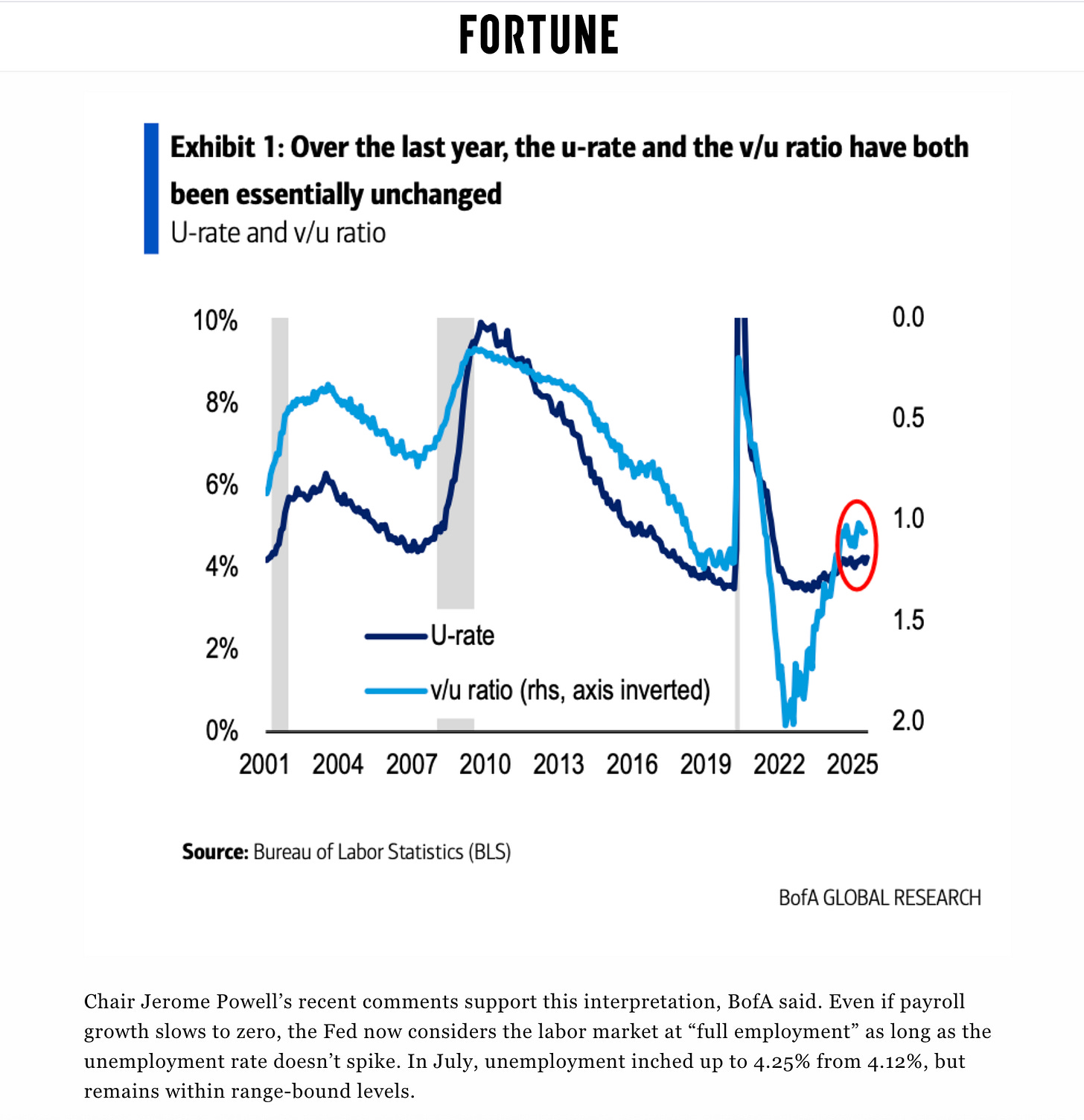

This supply-side squeeze is pushing against weaker labor demand, keeping metrics that should indicate labor slack - such as the unemployment rate and the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed workers - basically flat for the past year.

Bank of America estimates that break-even job growth, meaning the rate of hiring needed to keep joblessness steady, will hit just 70,000 per month this year.

Nordea Bank Research observes that foreign-born workers have fallen by as much as 1.6 million since March.

So far this year, the number of foreign workers in the US clearly declined more than the estimated number of deportees (around 200,000). This means that there are even more people voluntarily leaving the US.

If this trend continues, break-even job growth could fall to just 10,000 jobs per month by the end of 2026, or even turn negative.

The economists at UBS, however, are of the opinion that the US labor market is showing signs of “stall speed”.

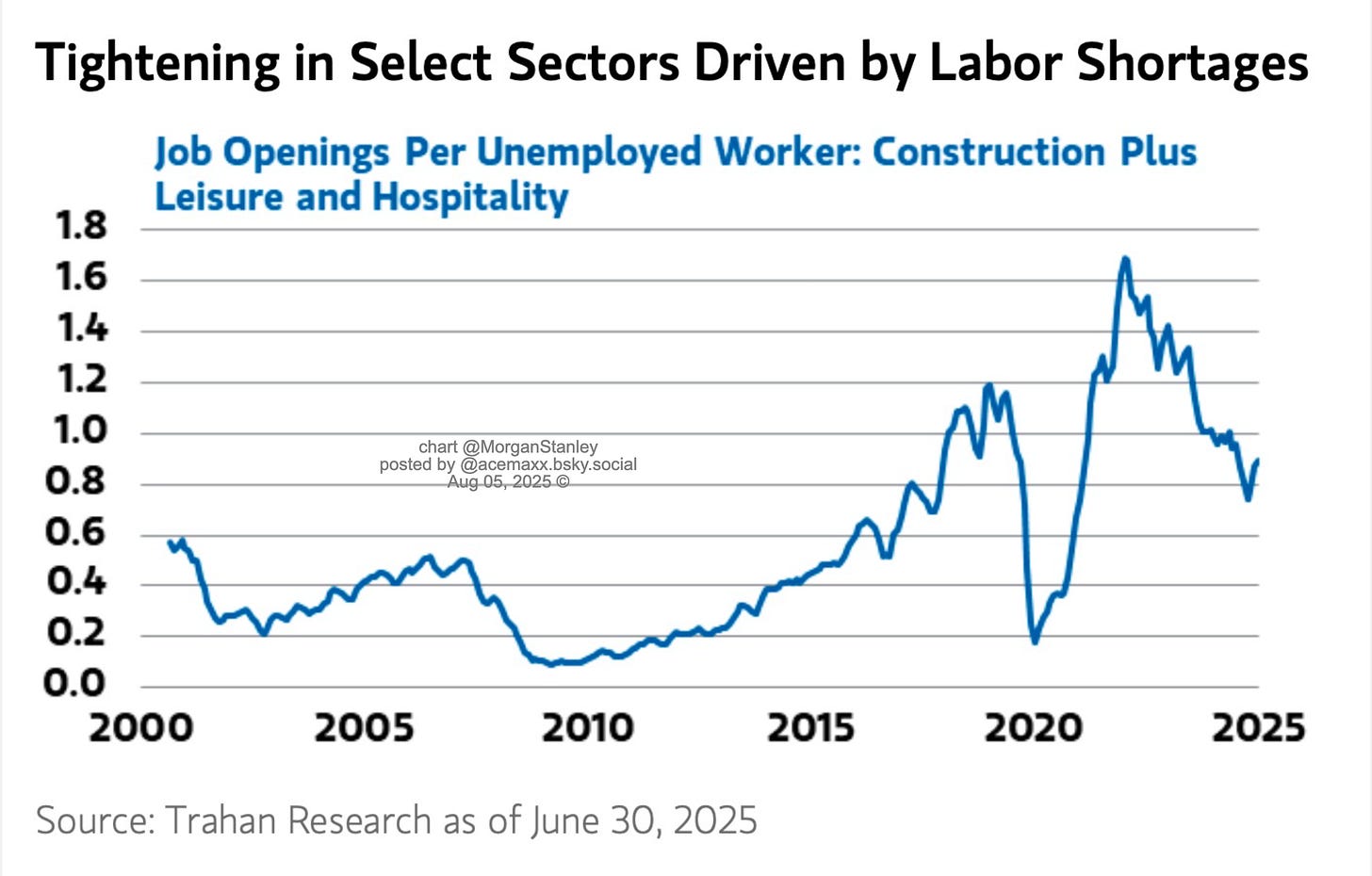

It is according to the note far from the “stretching” that’s typical when labor markets are tight owing to worker shortages. Industry-specific data also show that job losses are not concentrated in sectors with large immigrant workforces, further supporting the view that slack comes from weakened demand, not a supply constraint.

What BofA is saying is that

The US workforce = native-born workers (about 77–78%) + foreign-born workers (about 22–23%).

And we know what happened lately:

Native-born employment has grown (more people working in that group).

Foreign-born employment has shrunk a lot — by more than the native-born gains.

The net effect: total employment has fallen, even though the majority group (native-born) is growing.

Think of it like this:

Native-born: +500k jobs

Foreign-born: –1.0 million jobs

Net change: –500k jobs

So BofA’s point is: the losses in the smaller group (foreign-born) have been so large that they outweigh the gains in the bigger group (native-born).

Why this is tricky for the Fed:

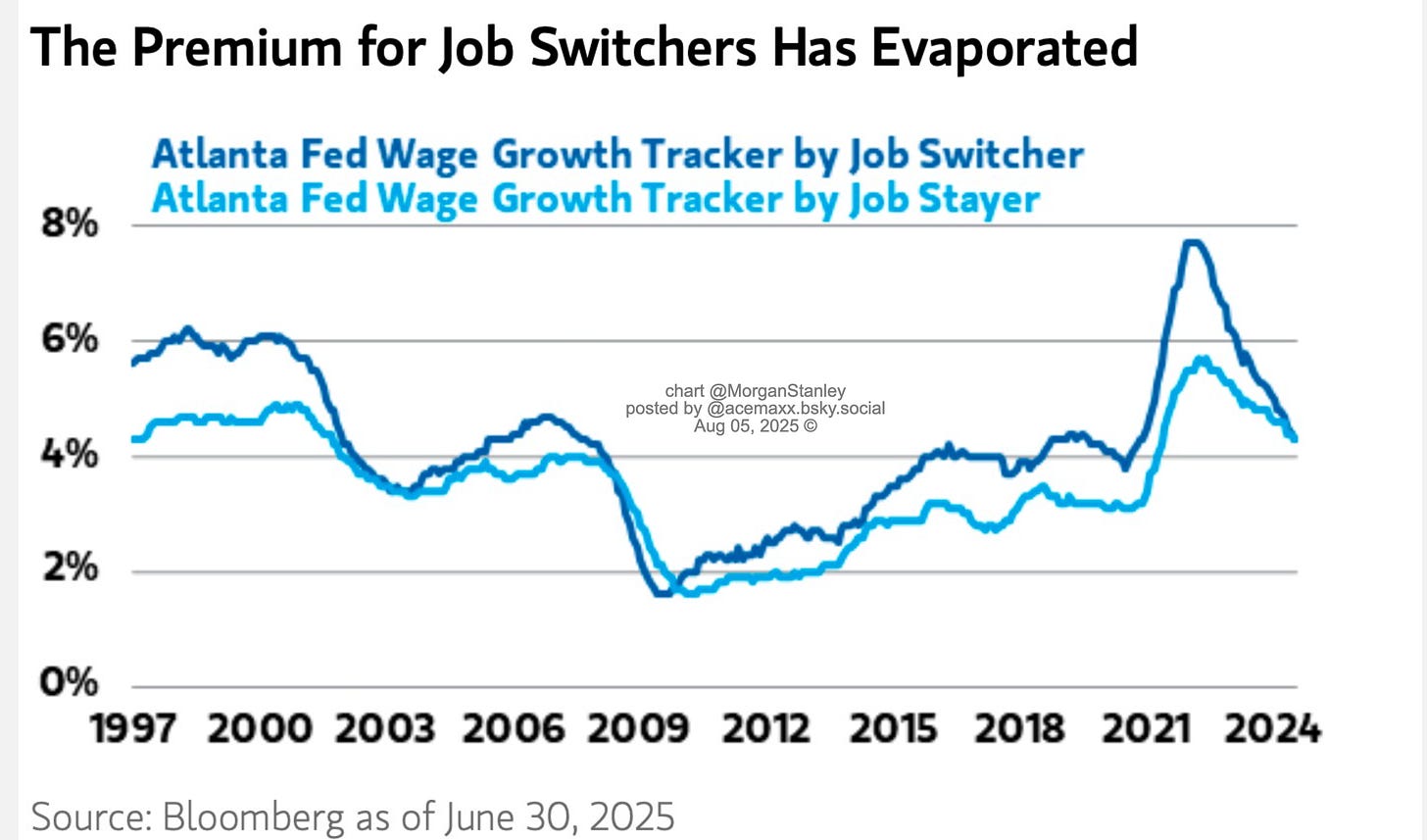

A collapse in foreign-born labor supply looks like tightness in the labor market (low unemployment, wage pressures).

But if GDP growth slows because there simply aren’t enough workers, the Fed faces a stagflation signal — slow growth and inflationary pressures.

The correct policy response depends on diagnosing the source:

Supply-driven stagflation → rate hikes won’t fix it, could make growth worse.

Demand-driven weakness → easing might help, but risks stoking inflation.

Why the demand vs. supply framing matters:

If you see the drop in foreign-born workers as a supply-side shock:

Labor supply is shrinking, so the economy can’t produce as much.

This can push up wages and prices, even without strong demand — classic stagflation risk (low growth, high inflation).

The Fed’s problem: raising rates won’t create more workers, but it can crush demand, worsening the growth slowdown.

If you see it as a demand-side problem:

Weak job growth is due to companies not hiring because demand is soft.

Here, the Fed might have room to ease policy if inflation is under control, because more demand could bring employment back up.

In other words:

BofA is flagging that who is leaving the labor force matters as much as how many, and the Fed needs to decide whether this is mostly a labor-supply shock (structural) or a demand shortfall (cyclical). That choice changes the rate policy path entirely.

Excursus:

What “declining break-even job growth” means:

Labor force growth slows - due to less immigration, retirements, or weaker population growth.

The number of jobs needed each month to keep unemployment steady drops — maybe from ~150,000/month historically to near zero, or even negative.

In this environment, even slow or flat job creation won’t push the unemployment rate up, because there are fewer new workers entering the market.