Real Devaluation versus Fair Competition

Why the krone is weak despite Norway’s wealth

Norway is one of the world’s richest countries, with vast oil wealth, a sovereign wealth fund worth nearly $2 trillion, and a 17% current account surplus — yet its currency, the krone, has steadily depreciated.

The puzzle of a rich country with huge surpluses and a weak currency almost begs the question: is someone quietly pulling the strings?

To an outside observer, it can look as if Norway is deliberately holding down the krone (NOK):

Huge current account surplus.

Currency persistently undervalued.

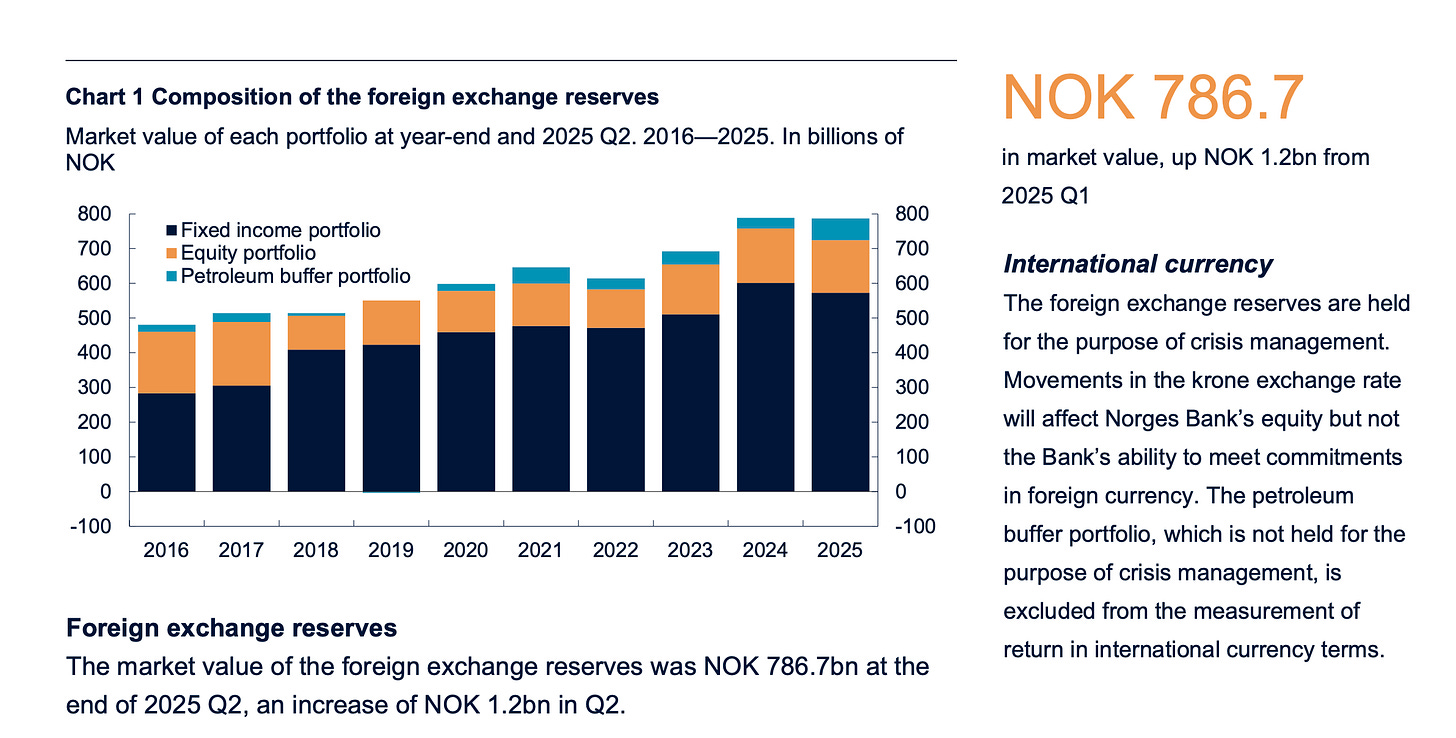

Rising reserves.

Heiner Flassbeck points out:

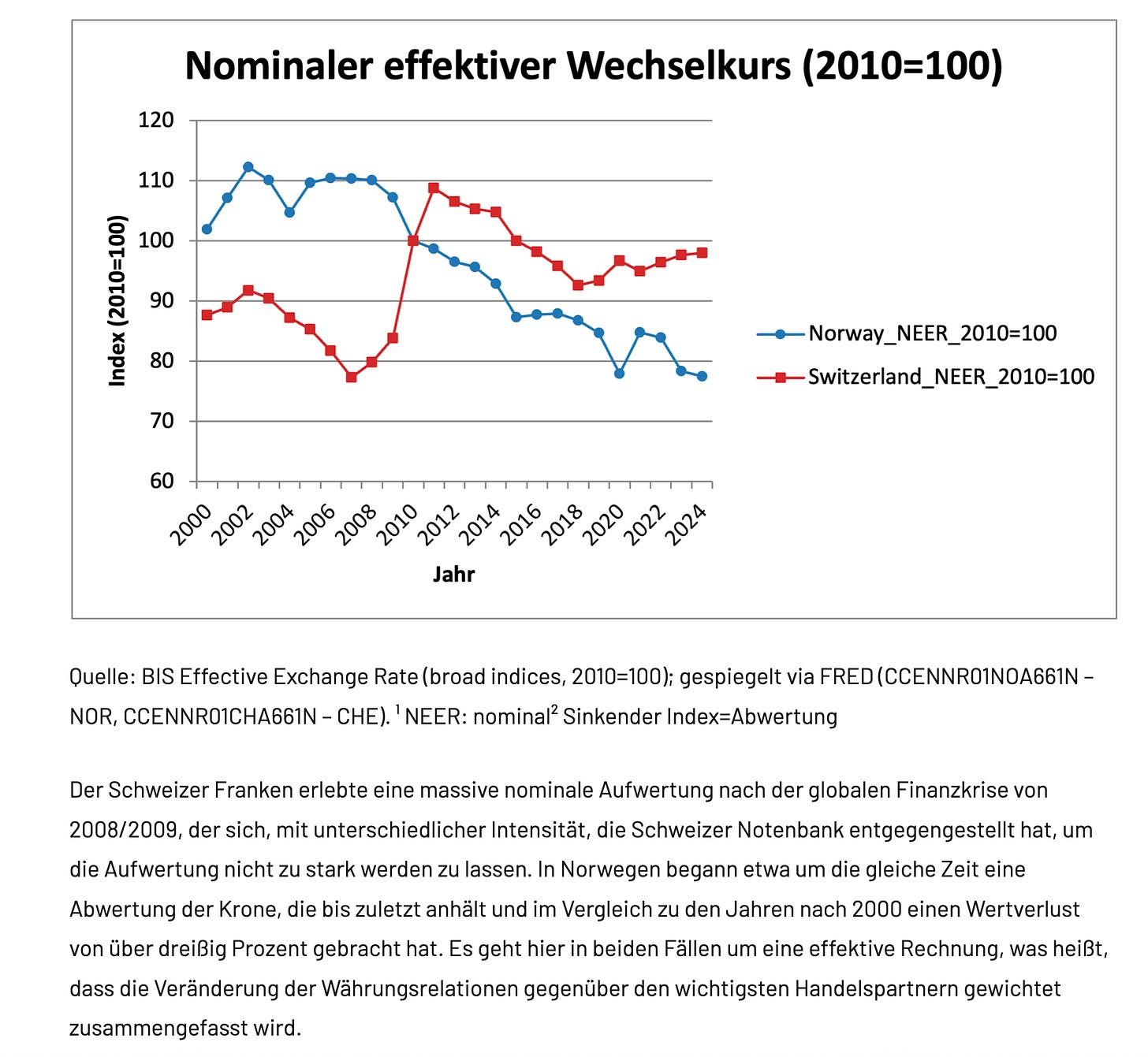

Norway is improving its competitiveness year after year, although there is no evidence that it has ever lost significant competitiveness before. The current account (CA) surplus, which is a (albeit crude) indicator of a country's external position, was over 10% of GDP from 2000 to 2012, which is an enormously high figure.

The former Chief Economist (Chief of Macroeconomics and Development) at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva, from January 2003 to the end of 2012, adds:

There is little evidence that the development of Norway's foreign exchange reserves can be explained by normal FX market activity. The interplay between a weak krona and rising reserves is all too clear. After all, Norway's FX reserves reached 20% of GDP in 2020, which only seems small compared to Switzerland's absolutely exceptional figure.

Let’s break it down carefully.

The Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) channel

When Norway sells oil & gas abroad, the revenues first come in as dollars, euros, etc.

Instead of converting all that into krone (which would strengthen NOK), the government transfers most of it into the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG).

The GPFG then invests only abroad — in global equities, bonds, real estate.

That creates a systematic capital outflow, year after year.

Result: Permanent downward pressure on NOK demand.

Market perceptions & liquidity

The krone is a small, illiquid currency. Traders know daily flows are thin.

That makes it highly sensitive to risk sentiment: when global investors get nervous, they dump NOK first, regardless of fundamentals.

Oil dependence adds to this “petro-currency” label, so when oil prices fall (or even just wobble), NOK sells off disproportionately.

Policy tolerance

Norges Bank targets inflation, not the exchange rate.

A weaker krone helps reach the 2% inflation target and supports exporters.

So, the central bank does not resist krone weakness — if anything, it sometimes welcomes it.

Yet there is no doubt that a persistent undervaluation by a wealthy, resource-rich economy can harm trading partners, especially developing countries whose export competitiveness suffers.

Norway might not be actively manipulating its currency in the classic sense. The weak krone seems the result of structural capital outflows to the SWF, thin FX markets, and investor perceptions.

This means: most foreign currency inflows from oil exports are sterilized (converted into foreign assets) rather than converted into NOK for domestic circulation. (*)

But the effect is real: a persistent real depreciation that benefits Norwegian exporters and, imposes costs on trading partners. In a rationally organized global monetary system, such imbalances would be barely tolerated — but today, unfortunately they remain part of the “rules of the game.”

Yet as Prof. Flassbeck further argues, Norway has largely exploited its fossil fuel reserves without regard for the climate, but now believes that, as a so-called ambitious country, it can put pressure on developing countries to refrain from promoting fossil fuels.

That can never pan out. Only when those who have profited massively in the past give up part of their fossil fuel wealth in favour of the poorest people on earth can there be hope for real change.

(*)

This keeps demand for NOK structurally lower than it would otherwise be, which has a similar effect to deliberate FX intervention. The institutional design of the SWF functions as a permanent anti-appreciation device, which is a very sophisticated way of dealing with «Dutch Disease».

(**)

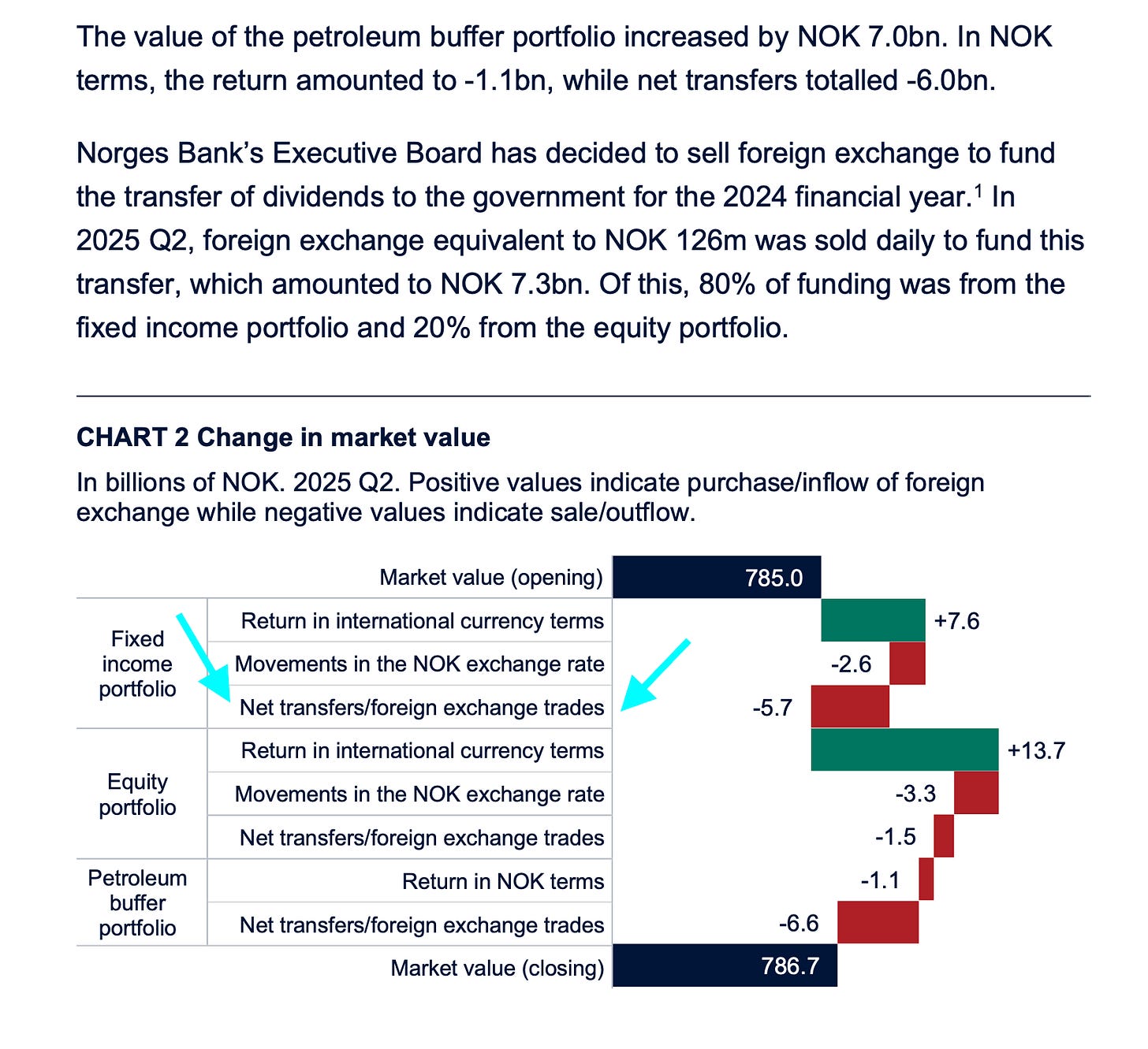

What the chart means:

The returns show that the fund’s international investments made gains.

NOK FX effect shows that because the krone strengthened slightly, those foreign gains look a bit smaller when translated back into NOK.

The net transfers reflect how much new oil money was converted from NOK into foreign currency and invested abroad — this is the structural outflow channel I discussed earlier.

So when the line says “–5.7 bn NOK net transfers/FX trades”, that means the fund sold NOK, bought foreign currency, and invested it abroad. The petroleum buffer portfolio’s –6.6 bn NOK is basically oil revenues being siphoned into the fund.

PS: Norges Bank highlights this:

The FX are the Bank's contingency funds in international currencies and are to be available for use in foreign exchange market transactions as part of the conduct of monetary policy or with a view to promoting financial stability and to meet Norges Bank's international commitments.