Over the past 10 years, there has not been much incentive to invest in government bonds other than US Treasuries. UST yields were competitive and the USD was strong.

Now the environment has changed significantly. The returns on foreign government bonds when converted back into USD (after hedging) are surprisingly attractive for US investors.

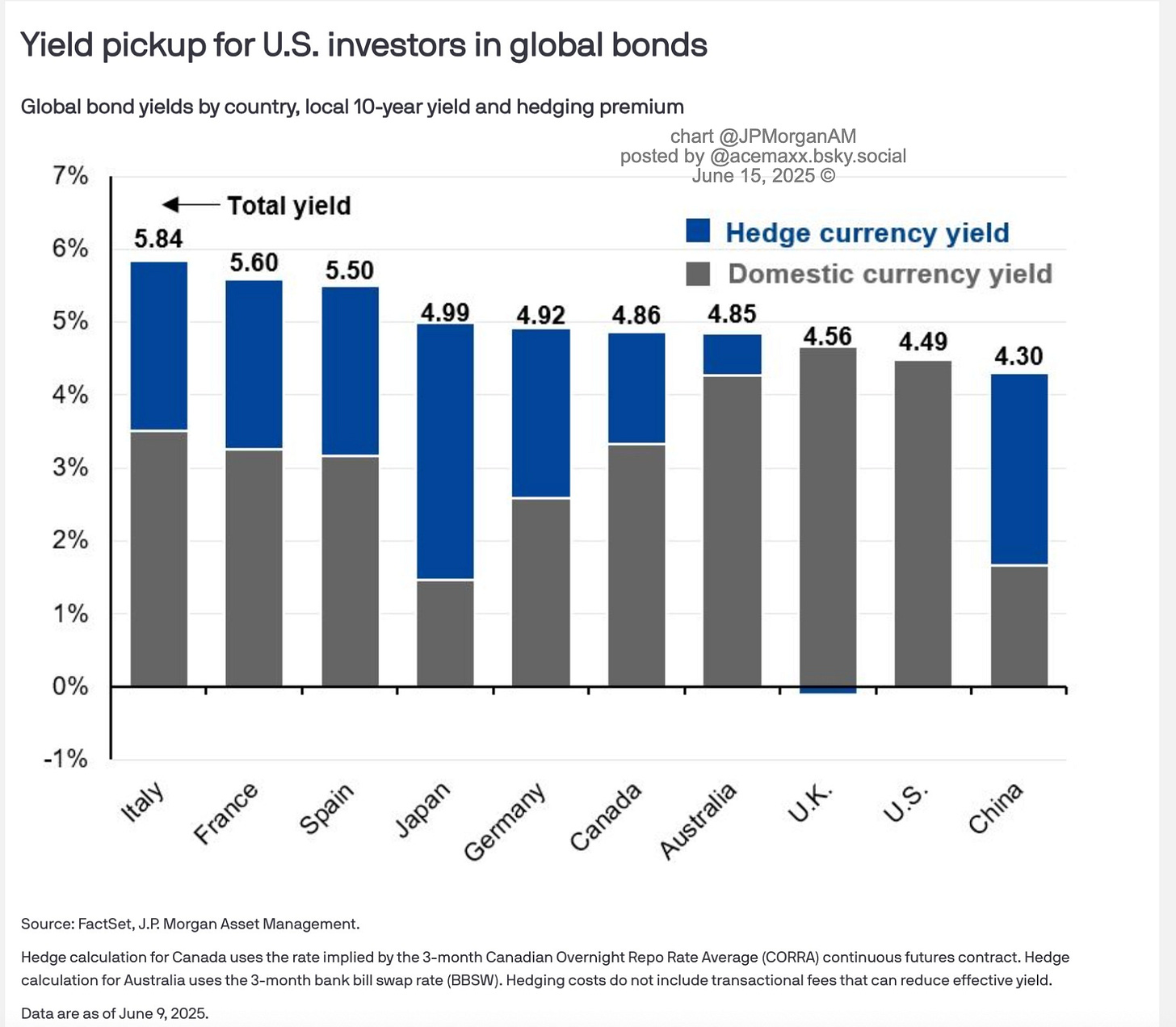

Given the current UST yield of 4.40%, the yield on foreign government bonds does not look attractive enough. However, if we take the hedging premium into account, the attractiveness of a number of government bonds in other industrialized countries increases.

According to JPMorgan AM’s recent research:

When a US investor buys foreign bonds, currency risk is typically hedged to avoid volatility from exchange rate movements.

The cost - or return - of that hedge depends on the interest rate differential between the U.S. and the foreign market.

When you hedge, you effectively "lend" at the US rate and "borrow" at the foreign rate- locking in the difference. This difference becomes your hedging premium.

An example:

10y JGB is yielding (per June 13, 2025) 1.40%, meaning under 2%. Yet Japanese Government bond delivers a total yield above 5% after including the hedging.

A similar dynamic also applies to government bonds from Europe and, in some cases, Asia.

The point is potential diversification benefits for international investors. Of course, investing globally is not without risk, as JPMorgan AM emphasizes.

What’s going on when a U.S. investor buys German Bunds?

Step 1: You buy a foreign bond (e.g., a 10y German Bund denominated in euros).

But you’re a US investor, so your home currency is the USD.

The euro exposure introduces currency risk - if the euro weakens, your returns in USD fall, even if the bond performs well.

Step 2: You hedge the currency risk (using FX forwards or swaps).

This converts your euro cash flows back into dollars at a fixed exchange rate.

Now, your return is “clean” - no FX risk, just the bond’s yield plus/minus the cost of hedging.

So what’s the “hedging premium”?

It’s the profit or cost embedded in the currency hedge.

When you hedge currency risk, you're doing two things:

Lending in your home market (USD)

Borrowing in the foreign market (EUR)

The difference in those interest rates (short-term) is the hedging premium.

Formulaically:

Hedging premium ≈ U.S. interest rate – Foreign interest rate

If US short-term rates are higher than euro rates, you earn a positive hedging premium.

If euro rates were higher (e.g., pre-2008), you'd pay a hedging cost.

Example: German Bund vs. U.S. Treasury

Let’s say:

10y German Bund yield = 2.4%

10y U.S. Treasury yield = 4.4%

But you hedge the currency, and the euro short rate is 3.75%, while US short rate is 5.25%.

Now, the hedging premium is:

5.25% (USD) – 3.75% (EUR) = +1.5%

So you add that to the Bund yield:

2.4% (Bund) + 1.5% (hedging premium) = 3.9% USD-hedged yield

Suddenly, that “low-yield” Bund looks more competitive relative to the 4.4% UST - especially if the investor prefers the credit quality of Germany.

Why this matters:

Many institutional investors only compare hedged yields — this avoids FX noise and allows apples-to-apples comparisons.

In today’s world of interest rate divergence, hedging premiums can materially shift the relative value of global bonds.