Export Surpluses and Capital Outflows: Asia vs. Germany

Global Trade Imbalances

The comparison between Asia’s traditional export-to-invest-in-America model and Germany’s massive current account surplus with global capital outflows is insightful - both are «surplus economies», but they operate differently in terms of strategy, target markets, and financial integration.

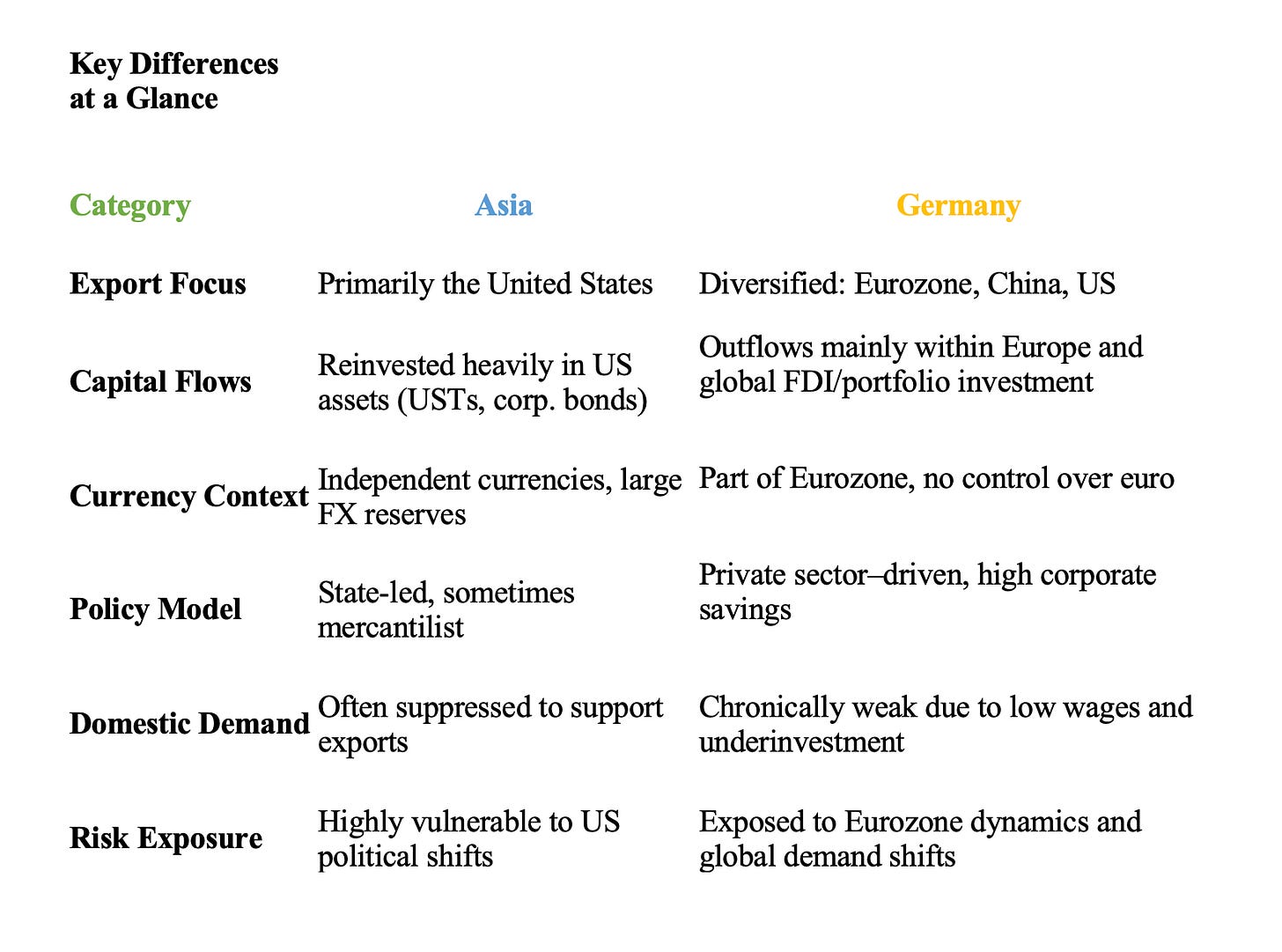

A breakdown of the main differences in terms of target of exports displays some striking parameters:

Asia (esp. China, Japan, South Korea):

Primarily export to the United States. Their export-driven growth relies on American consumer demand and the stability of the US dollar.

Germany:

Exports heavily to European neighbors and global markets (including China and the US), but its surplus is more geographically diversified than Asia's traditional US focus.

There is also a difference in terms of capital reinvestment strategy.

Asia:

Recycles export earnings directly into US dollar assets; primarily US Treasuries, corporate bonds, and real estate.

And Asian countries’ main motivations at this are:

Currency management: Prevent their currencies from appreciating (which would hurt exports).

FX reserves: Build a war chest to defend against crises (e.g. 1997 Asian Financial Crisis).

Liquidity and safety: US markets are the deepest and most liquid.

Germany:

Uses its current account surplus to fund capital exports primarily within the Eurozone (e.g., lending to southern Europe) and to a lesser degree to other global destinations.

Instead of buying large amounts of US Treasuries, German surpluses have often recycled through European banks, or into portfolio and FDI globally.

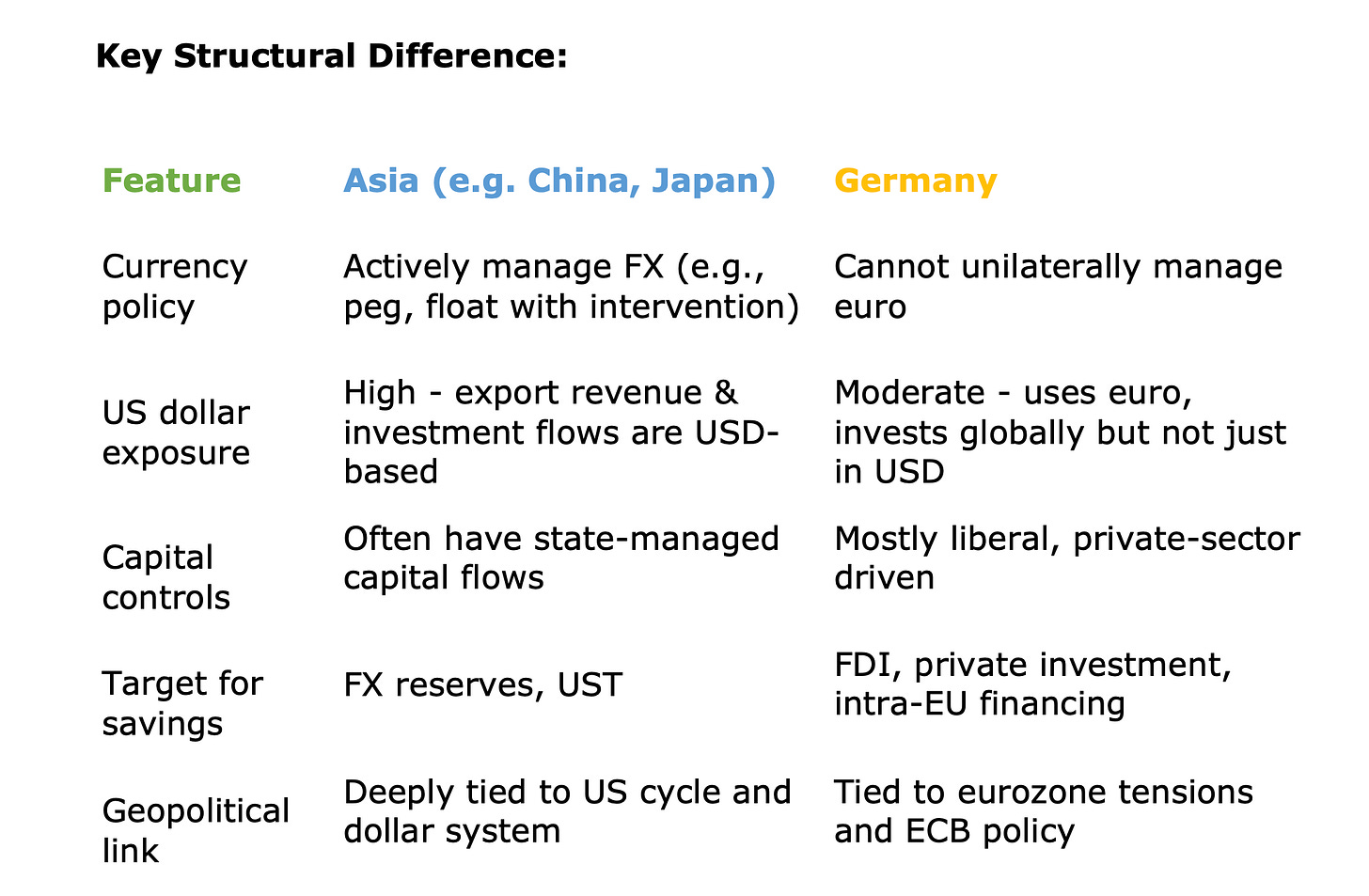

A look at the currency situation and monetary policy context reveals another interesting difference.

Asia:

Most surplus countries control their own currencies and accumulate foreign exchange reserves. Central banks often intervene in currency markets to maintain competitiveness.

Germany:

Is part of the Eurozone, meaning it does not control its own currency or interest rates. It benefits from a weaker euro than a hypothetical standalone German currency would allow, reinforcing its trade surplus.

Germany doesn’t accumulate reserves like China or Japan, its surpluses are private sector driven (e.g., savings by households and firms).

The structural driver of the surplus is also noticeable.

Asia:

Surpluses often stem from state-led strategies, mercantilist policies, high household savings, and managed exchange rates.

Germany:

Surplus is driven by a wage-suppressed, export-led model, with low domestic investment and consumption, and high corporate and household savings. German firms invest abroad, and domestic demand remains chronically weak.

The two approaches also differ in terms of political vulnerability.

Asia:

Trump’s tariffs, re-shoring, and possible financial decoupling pose a direct threat to the export-invest-in-America model, undermining both trade and the logic of holding $7.5 trillion in US assets.

Germany:

Faces EU-level constraints, geopolitical exposure (e.g. to China and Russia), and potential global backlash for its persistent surpluses.

However, it remains to be seen whether it is less exposed to an individual political decision-maker such as the US President.

The big-picture implication is that

Asia's model is being directly threatened by US policy shifts, tech decoupling, and financial weaponization.

Germany's model is under pressure from within - especially:

Eurozone imbalances (south vs. north)

Weak domestic demand

Calls to rebalance toward consumption and investment.

Yet both are grappling with the core dilemma of surplus economies:

Where do we put our savings, and/or do we even need such high savings in order to achieve social goals and raise living standards while ensuring a more even redistribution of income?