ECB’s Stealth Tightening

The fallacy of competitiveness via internal deflation

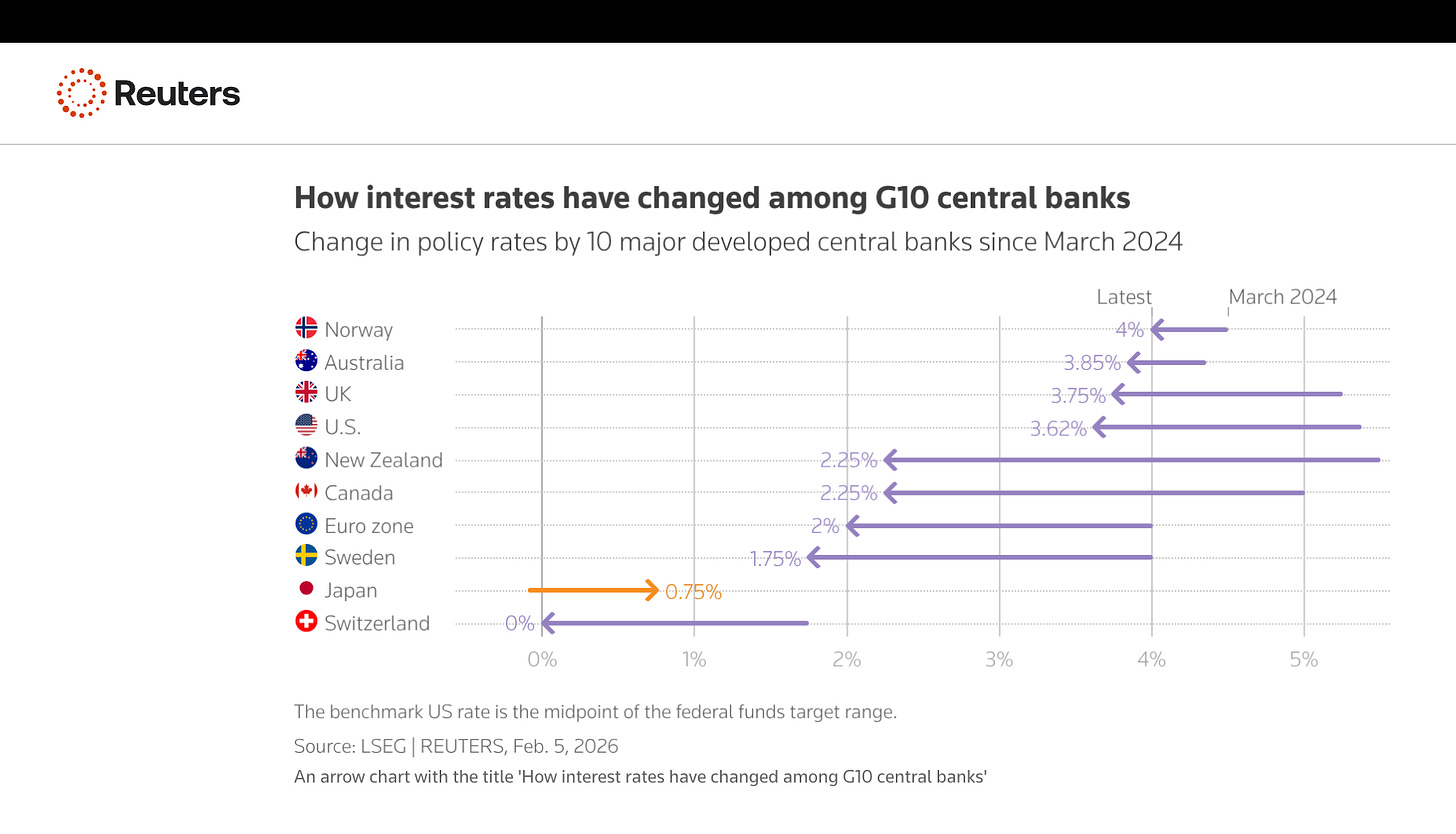

On Thursday, the ECB has decided to keep the three key interest rates unchanged.

The interest rates on the deposit facility, the main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility will remain unchanged at 2.00%, 2.15% and 2.40% respectively.

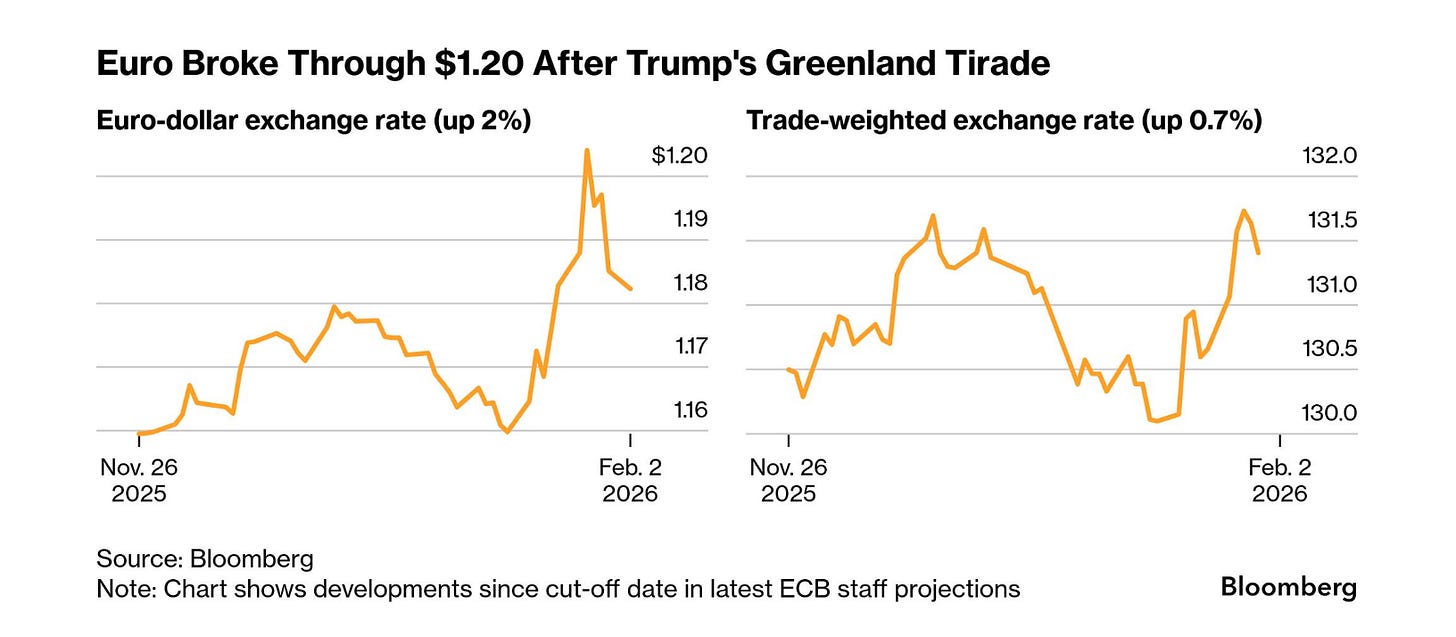

The subtext was hawkish. In the press conference, ECB president has emphasised – given the recent appreciation against the US dollar, that “we don’t target an exchange rate in terms of policy target”.

In other words, ECB policymakers are downplaying concerns about an overly strong euro.

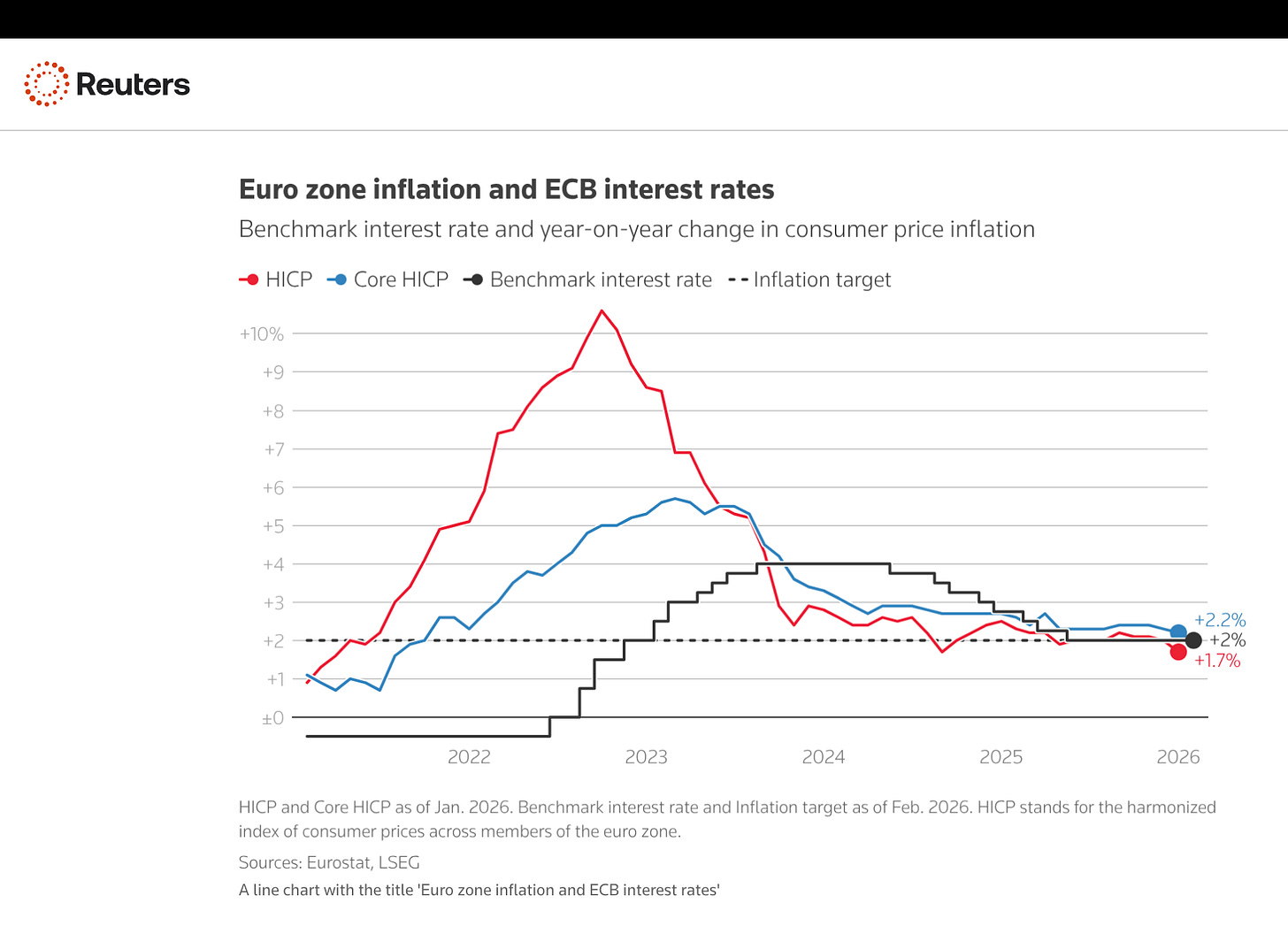

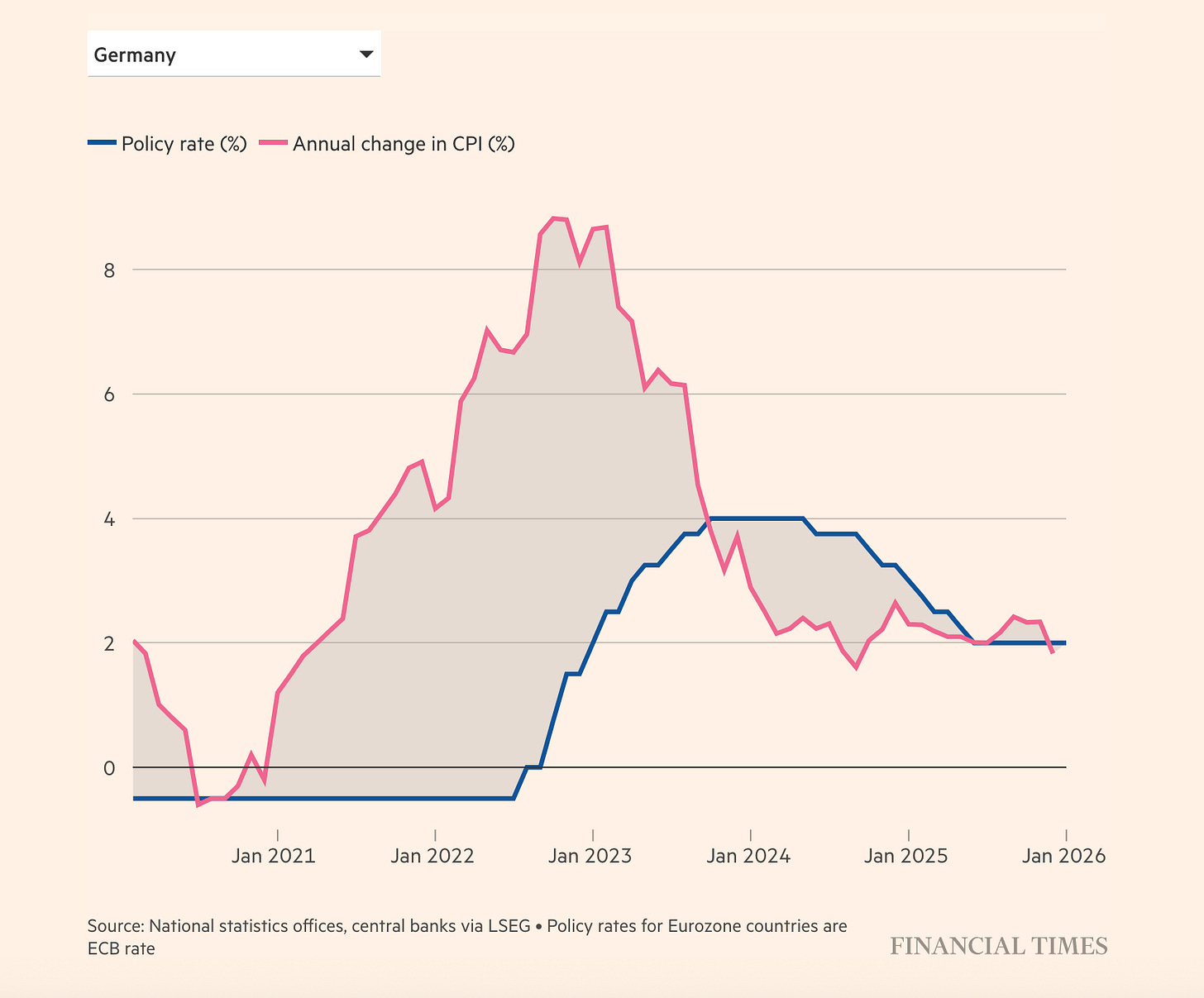

Moreover, Euro area annual inflation is expected to be 1.7% in January 2026, down from 2.0% in December according to a flash estimate from Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union.

With this in mind, the ECB seems to risk repeating a familiar European policy error: attempting to stabilise prices by suppressing domestic demand in an environment where inflationary pressures are already fading. When headline inflation is below target and producer prices are weak or falling, maintaining restrictive monetary conditions is not “prudence” — it is pro-cyclical tightening.

For Heiner Flassbeck, the fundamental nominal anchor of a currency union is:

Wage growth ≈ Productivity growth + Inflation target

If Eurozone wage growth moves toward:

Productivity (~1%)

Inflation target (~2%)

→ Wage growth ≈ 3%

If wage growth falls toward 2% or below, then structurally:

Domestic cost pressure collapses

Producer prices fall

CPI undershoots target

In that environment, restrictive monetary policy amplifies disinflation mechanically. Real interest rates are rising unintentionally. If inflation falls below target but nominal rates are not reduced:

Real rate = Nominal rate − Inflation

Example:

• Policy rate = 2%

• Inflation = 1.7% → Real ≈ +0.3%

• If inflation falls further → Real rate rises further

This is stealth tightening.

For investment decisions, real financing cost matters, not nominal rates.

So ECB risks tightening exactly when private investment is already fragile.

The point is that inside a monetary union, relative wage cuts do not create sustainable competitiveness.

Why?

Because:

• Exchange rate dominates external competitiveness

• If Europe compresses wages → inflation falls → ECB stays restrictive → euro appreciates → external competitiveness worsens

You get:

Domestic deflation + currency appreciation + weaker exports.

This is the classic internal devaluation trap.

When it comes to the sectoral balance problem.

If:

• Private sector = net saver

• External sector = surplus (EMU runs CA surplus)

Then mathematically:

Government must run deficits

or

Monetary policy must stimulate

If neither happens → demand gap → stagnation → disinflation → investment collapse.

If fiscal policy is constrained (Stability Pact, “Black Zero” thinking), then monetary policy becomes the only stabilisation tool. If the ECB also stays restrictive, the system has no stabiliser left.

Given the structural European policy bias, the ECB is embedded in a broader European ideology:

• Fiscal restraint obsession

• Household analogy (“Swabian housewife”)

• Fear of deficits rather than fear of unemployment

This produces a systematic asymmetry:

Aggressive against inflation

Passive against stagnation

The real risk: chronic low growth equilibrium

If policy stays restrictive while inflation undershoots:

Likely outcome:

Low nominal GDP growth

Weak investment

Low productivity growth

Rising political fragmentation

This is the Japanification risk, but without Japan’s fiscal stabilisation.

Bottom Line

If inflation is below target, wage growth is normalising, and the currency is strong, then holding restrictive monetary conditions is not price stability policy — it is de facto demand suppression.

In a monetary union without fiscal union, this is particularly dangerous because there is no automatic macro stabiliser at the federal level. Monetary policy must therefore err on the side of supporting nominal income growth, not suppressing it.