ECB: “We are in a good place” – Really?

The structural flaw in Europe’s economic governance

The eurozone economy is in a weak place — stagnant output, falling investment, and fragile demand — symptoms of a policy mix that prioritizes inflation over prosperity.

No wonder that ECB says «we are in a good place».

What is known for certain is that the ECB has only one mandate –

price stability. No mandate for full employment, as other

modern central banks around the world have; no goal for sustainable growth.

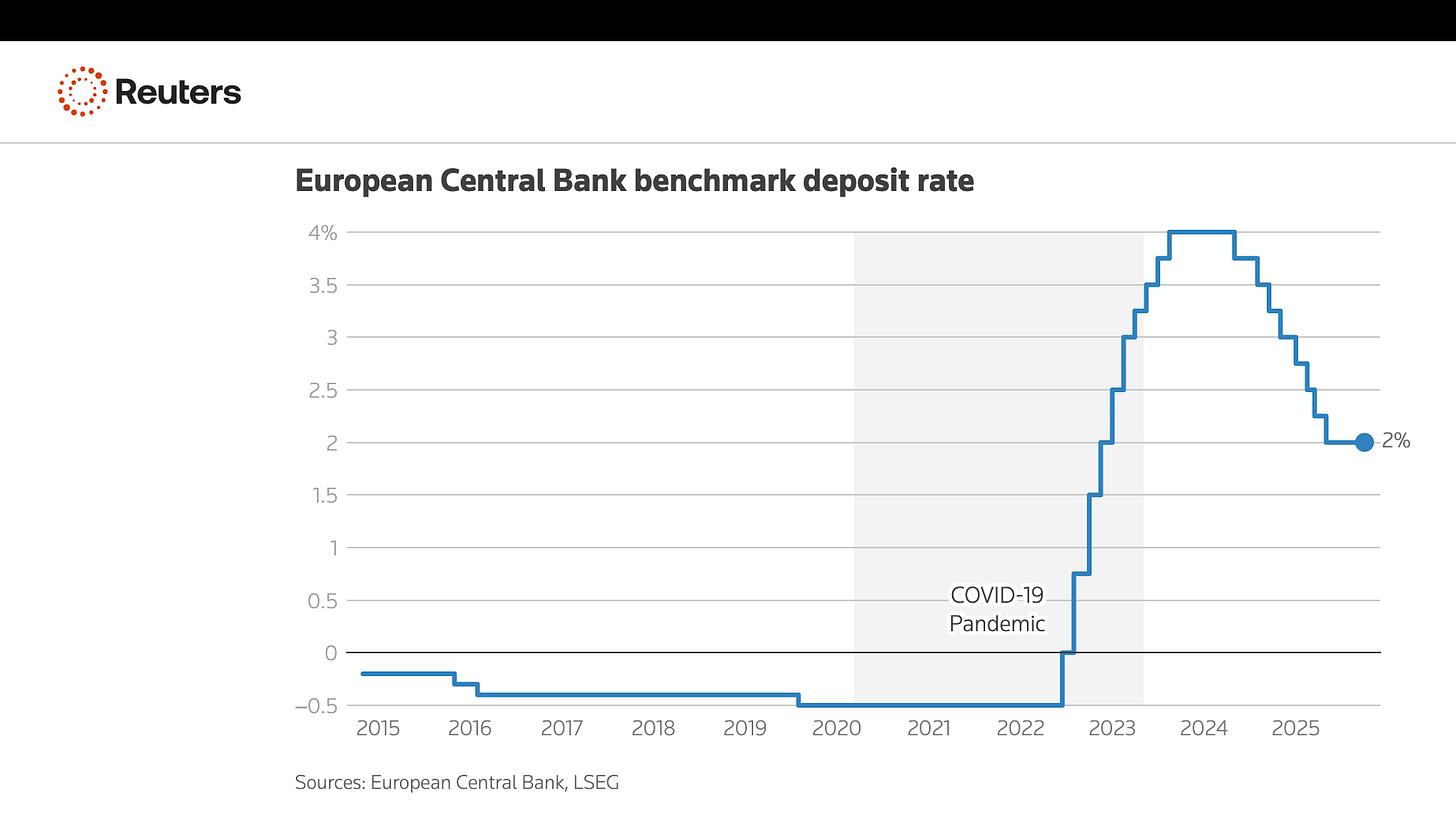

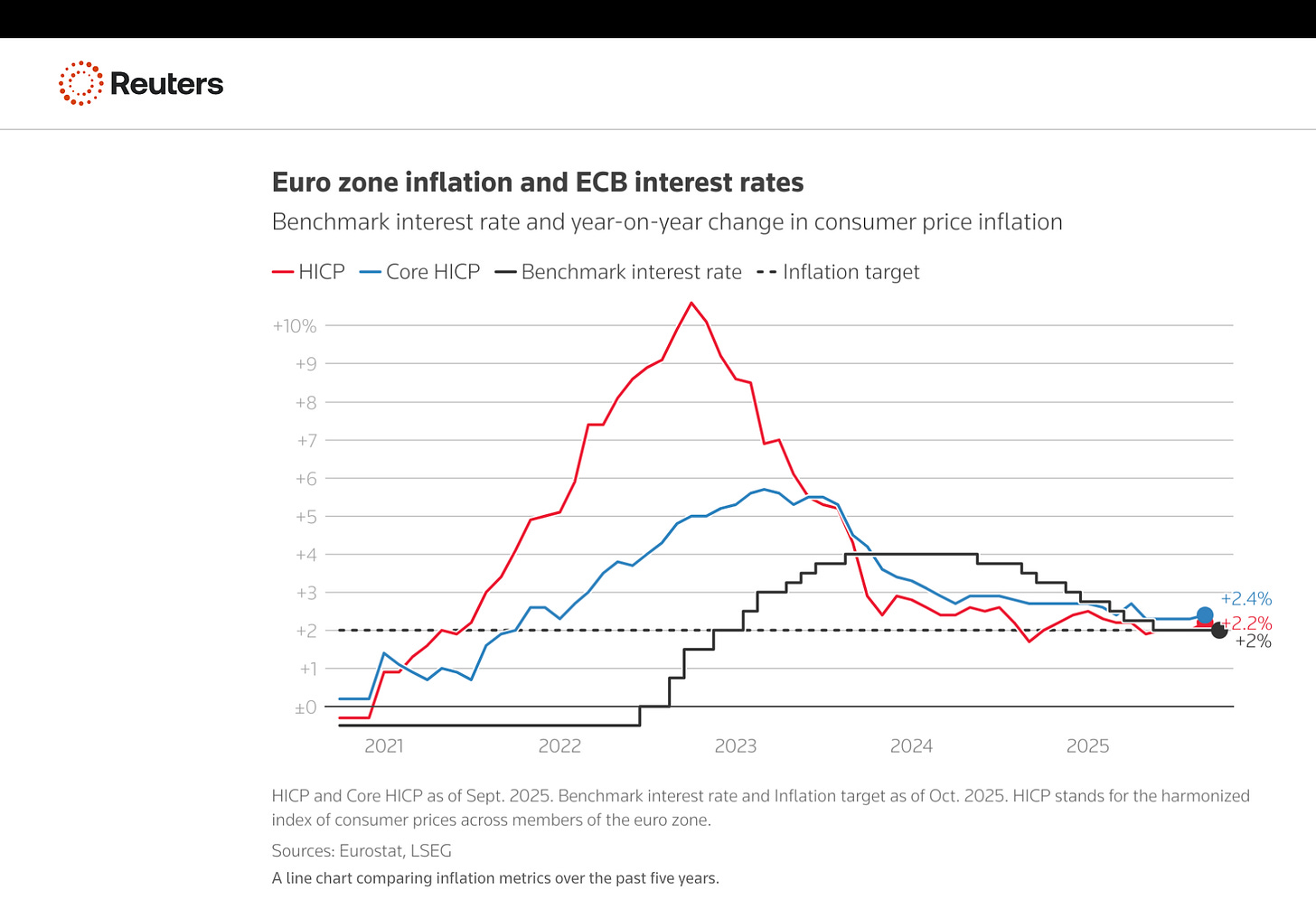

Yet the fact is the European economy is stagnating and underemployment is rising in more and more countries, while price stability has long been achieved.

So, European policymakers are not describing the real economy (weak growth, stagnant demand, sluggish investment), but rather the ECB’s own policy position within its «internal logic and constraints» (due to austerity obsession).

When ECB President or other ECB officials use such phrasing, they typically mean:

“We are comfortable with the direction and stance of our monetary policy given our inflation outlook.”

In other words: The ECB’s priority ≠ economic growth.

Again, here’s the crux:

The ECB’s mandate is price stability, not growth, jobs, or investment.

Even if the economy is weak, as long as inflation is not too low, the ECB will claim success.

So “good place” reflects stabilizing inflation dynamics, not living standards.

In its internal model, falling consumption and investment are even proof that the restrictive stance is working — they are “cooling demand,” which helps bring inflation down.

But here is the macroeconomic contradiction

Germany is stagnating (flat GDP, weak exports, industrial malaise).

The euro area as a whole is barely growing (~0.5%).

Real wages have only recently stopped falling after two years of decline.

Investment is collapsing under high financing costs.

From a demand-side perspective, this means monetary policy is too tight.

The ECB is, in effect, congratulating itself for causing this slowdown.

So, when they say “we’re in a good place,” you could translate it as:

“We’ve successfully slowed the economy enough to stop inflation — without (yet) causing a full-blown recession.”

Why they keep talking this way?

There are several motives:

Communication strategy

Institutional self-justification

Political insulation

Yet the ECB’s language reveals the structural flaw in Europe’s economic governance:

The central bank tightens demand to fight inflation.

Fiscal policy remains constrained by deficit rules.

No institution is responsible for maintaining adequate demand or employment.

So Europe ends up in a “policy equilibrium” that’s stable for prices but bad for growth — and the ECB calls that “a good place.”

Bottom Line:

It’s a strange definition of “good” when Europe’s largest economy is stuck in stagnation, households are still poorer than before the inflation surge, and investment has collapsed because corporations are net savers.

In truth, the central bank is celebrating (by the light of austerity fetish) a slowdown it helped create. By strangling demand to tame inflation, it has mistaken exhaustion for equilibrium. The eurozone now faces the quiet danger of long-term underinvestment, underemployment and social fatigue — the price of a technocratic complacency that confuses stable prices with a healthy economy.

The ECB may feel “in a good place.” Ordinary Europeans, clearly, are not.