Don’t Trust low Unemployment Numbers

Part-Time employment isn’t about “lifestyle choice”

Every time I hear from the mainstream media that the rise in part-time work is a “cultural shift toward more leisure time,” it makes me skeptical.

In my opinion, it is is strongly linked to austerity-driven weak demand, precarisation of labor markets, and inadequate social policies.

In other words, the rise of part-time employment isn’t just about “lifestyle choice,” as it’s often framed.

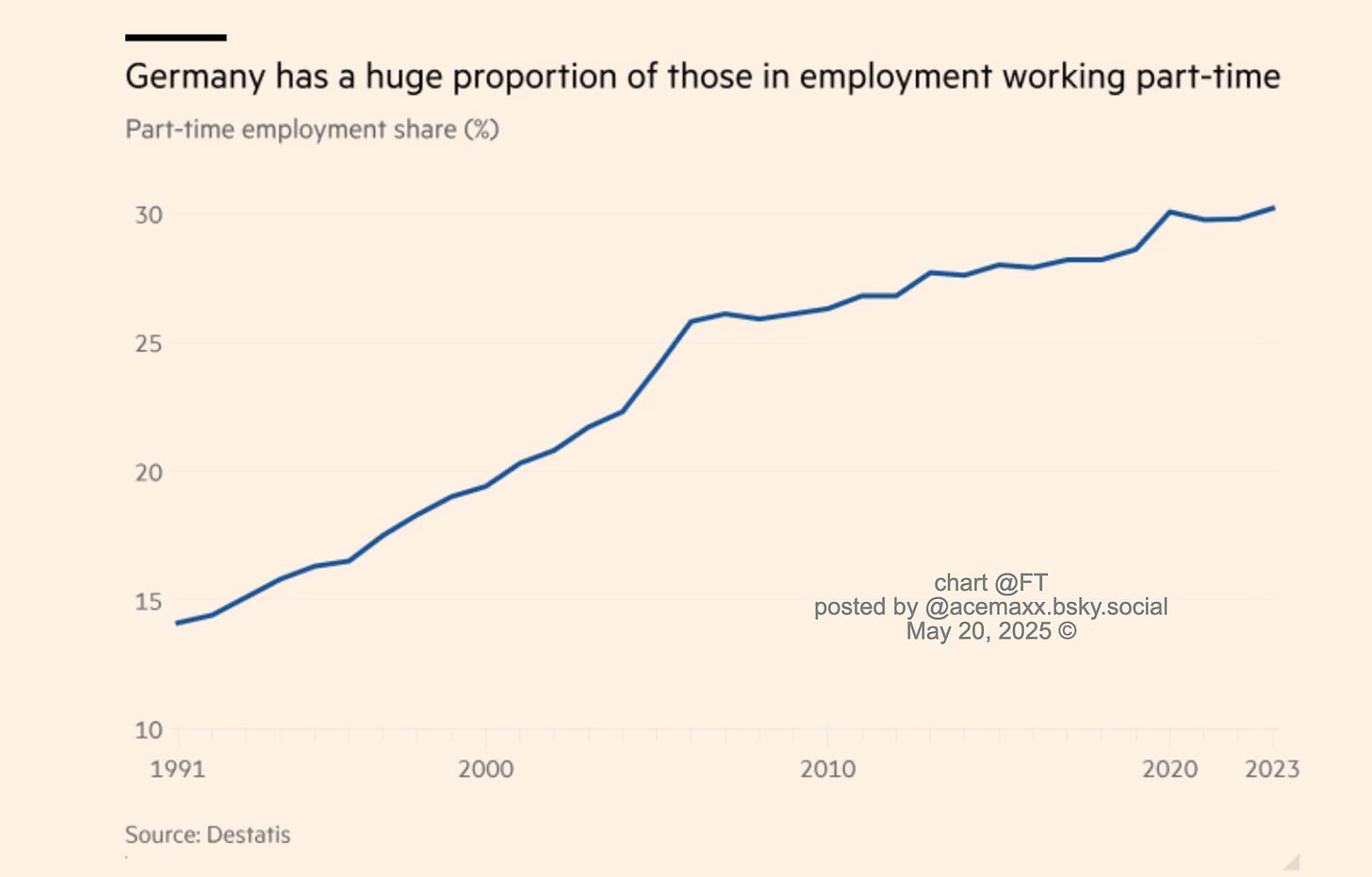

There are several deeper structural and policy-related reasons why part-time work has grown, especially in Europe since the 1990s.

Demand-side drivers (firms’ choices)

Austerity and weak aggregate demand:

Since the 1990s, and especially after the euro crisis (2010s), governments cut spending, firms saw lower demand, and investment slowed. Employers responded by preferring flexible, lower-cost part-time contracts rather than committing to full-time hires.

Cost control:

Part-time contracts often avoid full benefit obligations and reduce firms’ fixed labor costs.

Just-in-time labor: Companies facing uncertainty (globalization, tech disruption, austerity cycles) avoid long-term commitments and prefer “adjustable” employment.

Supply-side factors (workers’ side, but shaped by policy)

Women’s labor force participation:

More women entered the workforce, but in countries with weak childcare and eldercare infrastructure (Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands), many ended up in part-time roles. That’s not always “choice” — it’s an adaptation to inadequate public policy.

Older workers:

With rising retirement ages, part-time has become a way to keep older workers employed while phasing out.

Students and young workers: More are juggling education and work, especially where full-time entry jobs are scarce.

Policy and institutional shifts

Labour market “reforms” (1990s–2000s):

Many Western European countries made part-time contracts easier and subsidized them. Germany’s Minijobs are a classic example — promoted politically as “flexibility,” but effectively institutionalizing underemployment.

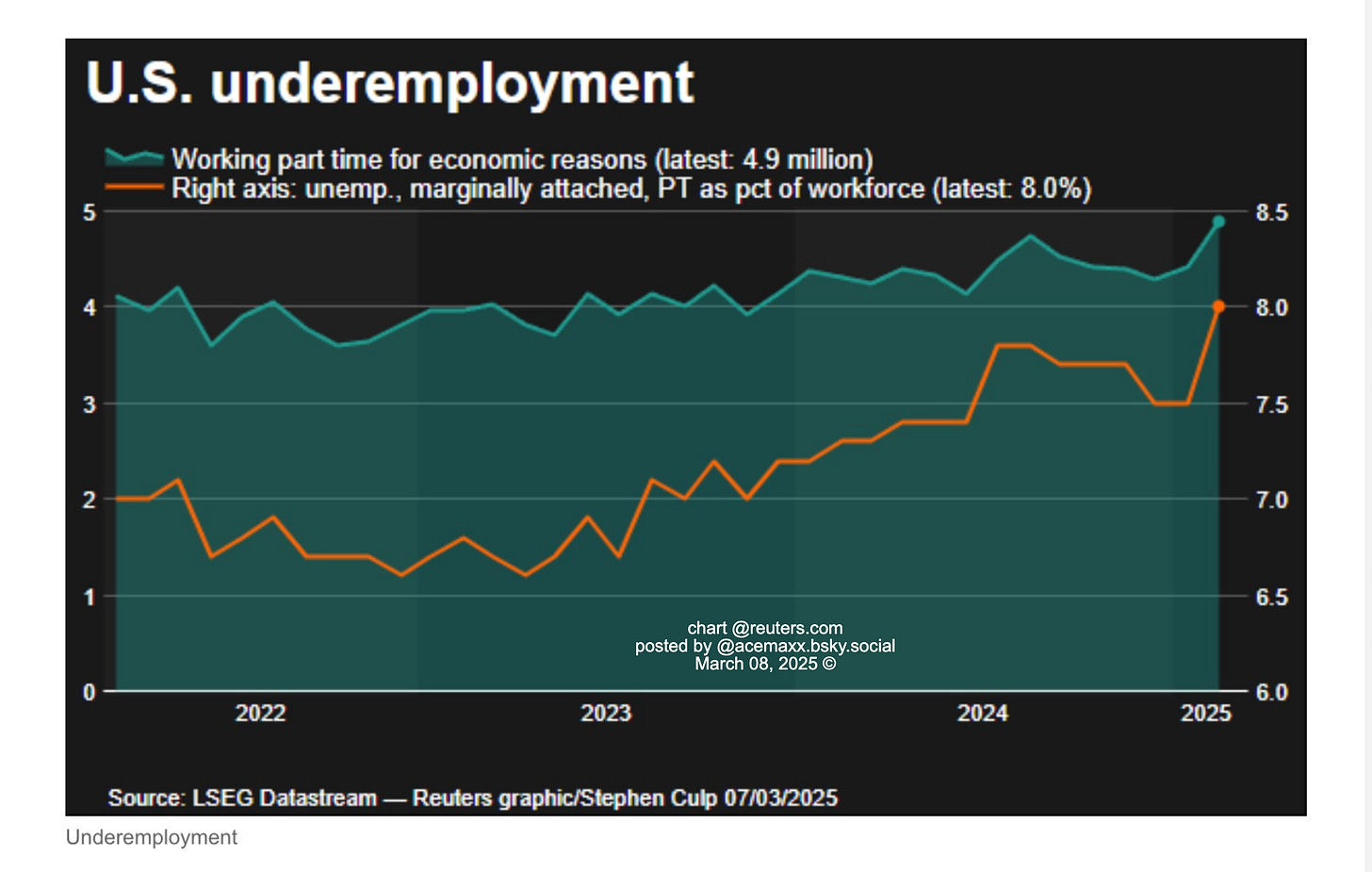

Prof. Danny Blanchflower and Alex Bryson show in a paper that rates of underemployment (the percentage of workers with part-time hours who would prefer more hours and the rate of inactivity (the percentage of the civilian adult population who are out of the labour force) reduce wage pressure in the USA.

The “voluntary” narrative vs. reality

Newspapers and policymakers often present part-time growth as lifestyle preference (“more flexibility, work-life balance”).

But data show that a large share of part-time is involuntary — people want more hours but can’t get them.

For example, Eurostat’s “underemployed part-time workers” are a major part of labour market slack.

In Italy and Spain, much of part-time is involuntary. In Switzerland or the Netherlands, it’s more “voluntary,” but shaped by structural childcare and social policy gaps.

Why men’s part-time is rising

This is particularly interesting:

Industrial restructuring: Manufacturing jobs (traditionally male, full-time) have declined, replaced by service jobs with more part-time arrangements.

Precarisation: Gig economy and temp contracts blur the line between full-time and part-time.

Care responsibilities: Slowly, more men are reducing hours to share family duties — though this is still minor compared to women.

Austerity trap: In tight labor markets, many men simply can’t find full-time jobs and accept part-time.

The Bottom Line

The rise in part-time employment is strongly linked to austerity-driven weak demand, precarisation of labor markets, and inadequate social policies. It’s not simply a “cultural shift toward more leisure.”