China’s overcapacity

Impact: Deflationary or Inflationary?

The topic of “China’s overcapacity” is very present and complex in the mainstream media. At its core, it revolves around the issue that China can produce significantly more in many key industries than its own domestic demand can absorb, and then pushes these surpluses onto the world market.

This is not about general overcapacity in all Chinese industries, but rather specific sectors that have been and continue to be heavily promoted by the Chinese government.

These include, in particular:

1. Renewable energies: solar panels, wind turbines, batteries (especially for electric cars).

2. Electric vehicles (EVs): China is the world’s largest EV producer and has built up enormous production capacity.

3. Semiconductors: An area in which China is investing heavily to reduce its dependence on the West.

4. Steel and aluminum: Traditional industries in which China has long played a leading role and repeatedly struggles with surpluses.

There are many reasons for the overcapacity:

• Government subsidies: The Chinese government provides massive support to these industries through subsidies, cheap loans, land allocations, and tax breaks. The aim is to become the global market leader and achieve technological independence.

• Investment-driven growth: China’s economic model has long been based on massive investment, which has often led to the creation of capacity that exceeds actual demand.

• Weak domestic demand: Chinese household consumption expenditure is relatively low compared to other major economies. When domestic demand cannot keep pace with production capacity, export surpluses arise.

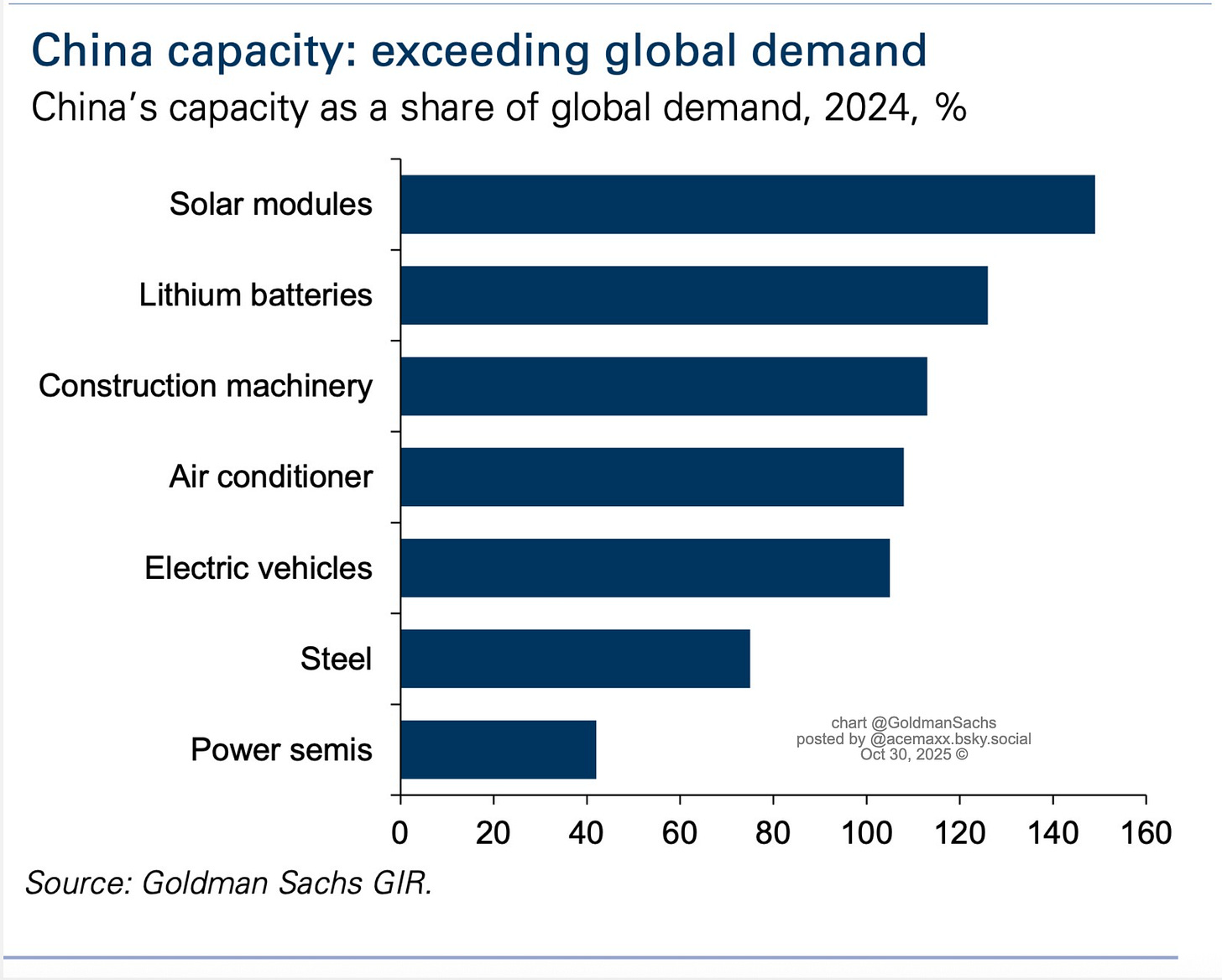

Against this background, Goldman Sachs Research underlines in a recently presented note that “China capacity is exceeding global demand”.

This means Chinese factories — particularly in industries like electric vehicles, batteries, solar panels, steel, and chemicals — can produce more goods than the world currently wants or can absorb.

China built this massive industrial capacity during its investment-driven growth phase, but domestic demand has weakened. So, these producers increasingly export the excess to global markets at very competitive prices.

Now, what are the “headwinds”?

If Chinese producers flood global markets with cheap goods:

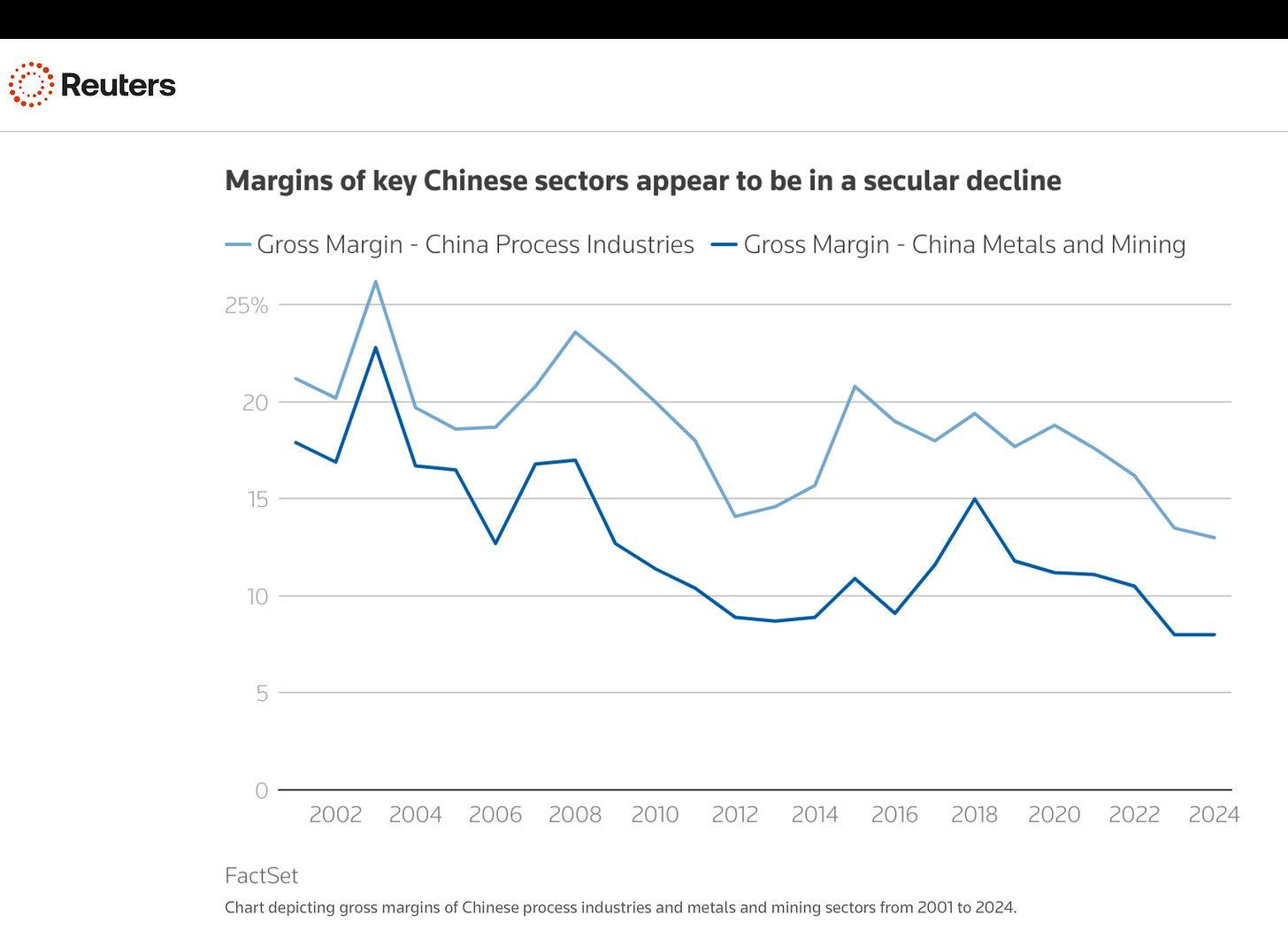

Prices fall globally (deflationary pressure in manufacturing).

Non-Chinese producers in the US, EU, Japan, and elsewhere lose market share and may cut production, profits, or employment.

Investment plans outside China may be scaled back because global prices are too low to justify new capacity.

So, “headwinds” means slower production and lower profits for manufacturers in other (mostly advanced) economies.

Goldman’s model estimate says:

If Chinese overcapacity continues to push down global goods prices and foreign manufacturing activity, then aggregate GDP growth in developed economies could be 0.1–0.3% lower per year than otherwise.

This drag happens through two channels:

Real activity channel → weaker manufacturing output, job losses, lower investment.

Price channel → imported disinflation reduces nominal revenues and profits (even if it helps lower inflation).

In short:

China’s overcapacity → cheaper exports → pressure on global manufacturing prices and output → reduced profitability & investment abroad → slightly slower GDP growth in advanced economies (about 0.1–0.3% per year).

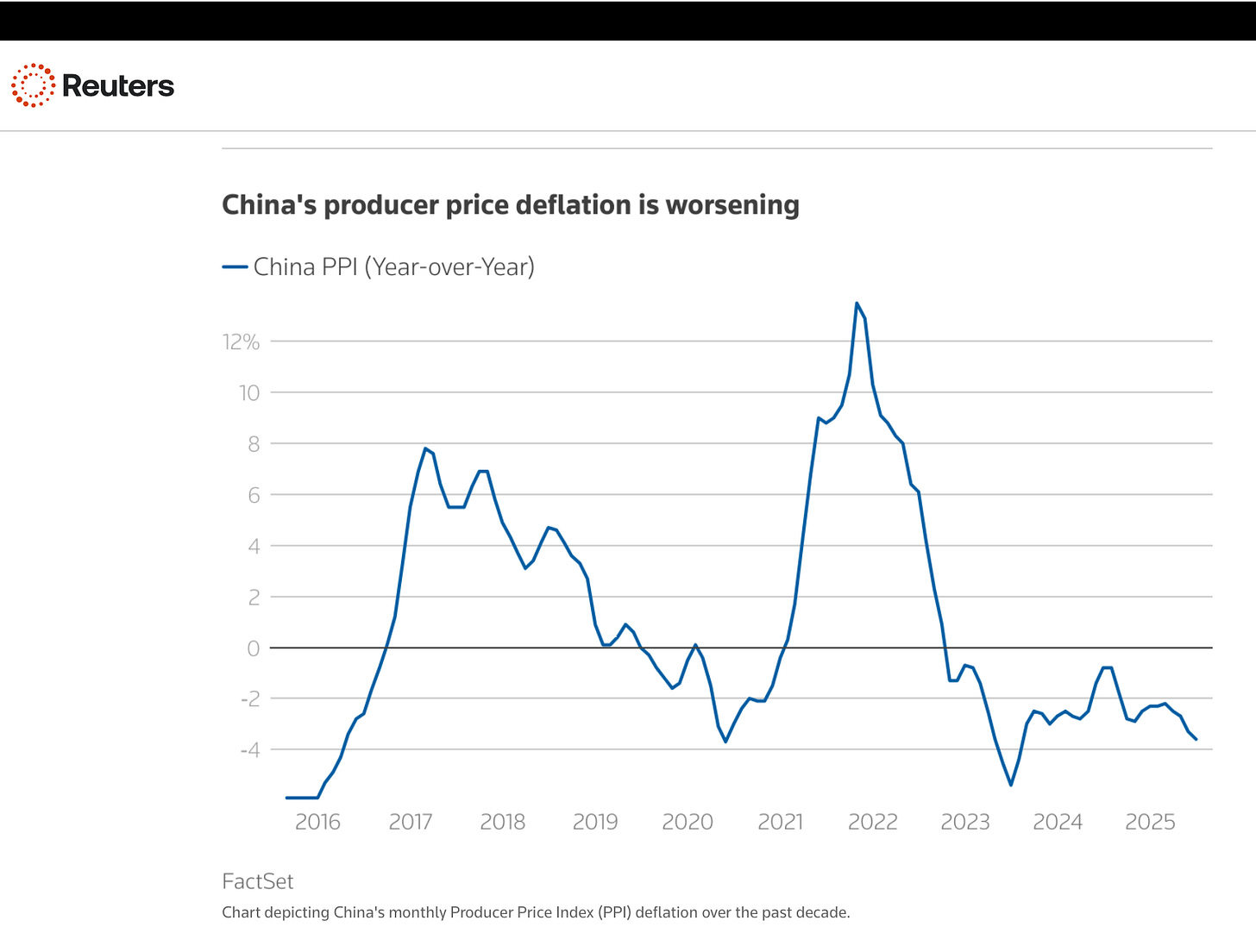

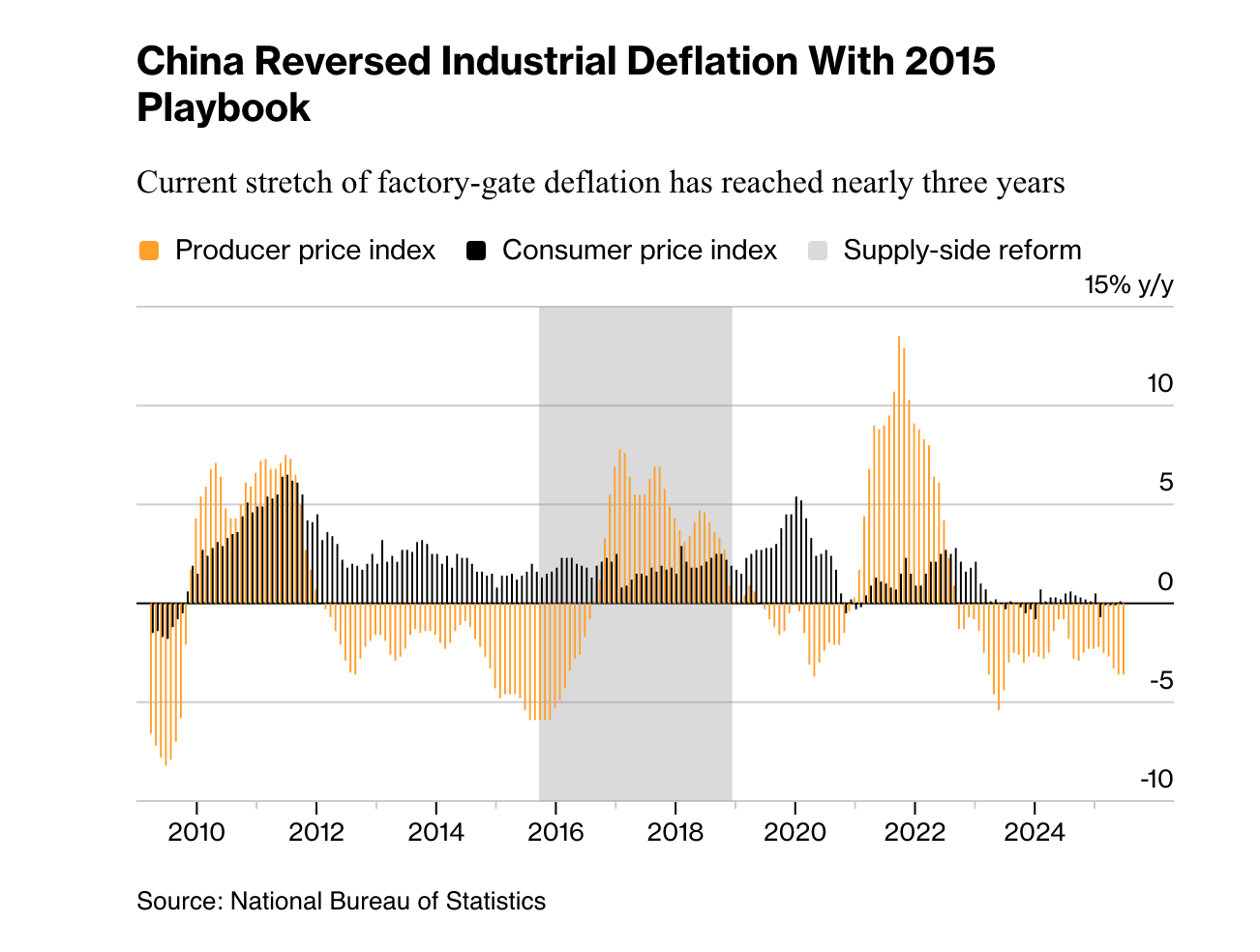

The immediate impact of Chinese overcapacity is primarily deflationary in the affected product categories.

In the long term and indirectly, however, there could also be inflationary tendencies if:

• Protectionism increases: If many countries impose tariffs, imports become more expensive, which can lead to inflation.

• Supply chains are reorganised: The “de-risking” of supply chains away from China could lead to higher production costs and thus inflation in the short term.

• Geopolitical tensions escalate: Trade conflicts and geopolitical uncertainty can affect energy and commodity prices.