Berlin Rails against 4-Day Week and Work-Life-Balance

The heated debate about allegedly lazy Germans, and women who only work part-time

Friedrich Merz, German Federal Chancellor identified a new issue:

“We need to work more again in this country”

Mr. Merz exclaims.

"We won't be able to maintain prosperity with a four-day week and a work-life balance"

But he is completely wrong. Four-day weeks are the exception in Germany, not the rule, as Alexander Hagelüken outlines.

Instead of cementing outdated gender roles, the government should rather encourage part-time employees to work more.

A comparison with other countries shows that there is potential to be tapped:

Germany has a particularly high number of short part-time jobs, 25 hours and less. In addition to better childcare facilities, financial incentives for those who want to work more could change this.

It is an open secret that the demographic personnel shortage can only be overcome if Germany attracts enough immigrants. However, Friedrich Merz has given the impression in recent months that migration is primarily a problem.

The logic behind proposals to extend working hours in a country like Germany, where wage restraint comes at the expense of productivity and underemployment is a constant issue, is questionable indeed.

In modern, advanced economies, prosperity is primarily driven by productivity per hour worked, not by the total number of hours worked. The post-WWII productivity miracle and the long-run historical trend of shortening working hours with rising wages demonstrate this well.

Germany, with one of “the highest productivity levels per hour in the world”, does not need more hours to generate prosperity.

About 5 million people in Germany are underemployed, either involuntarily working part-time or in precarious positions. This suggests that the issue is not a lack of total available labor, but an inefficient allocation of labor.

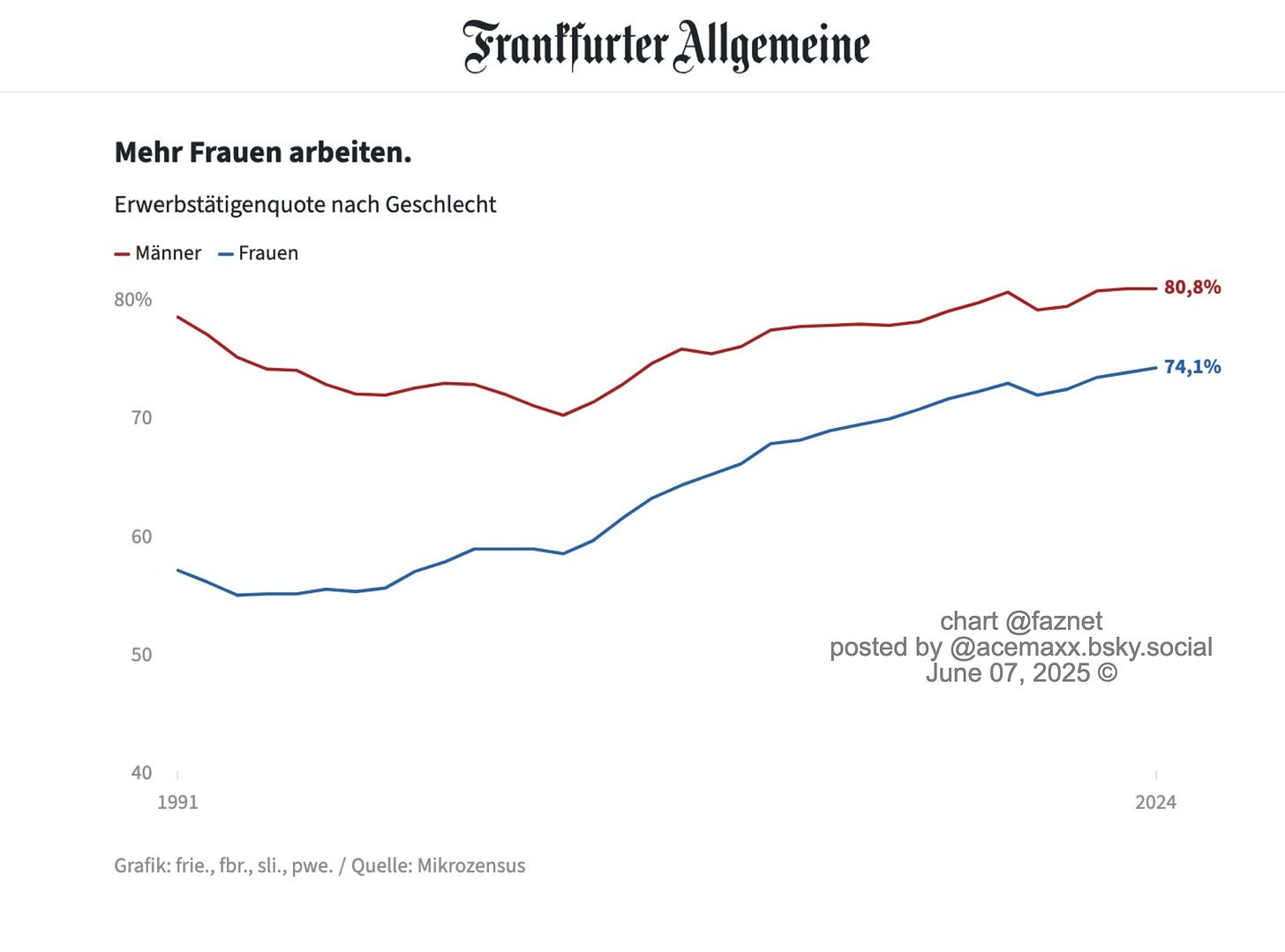

«The share of part-time workers has more than doubled to 30% of the labour force since the early 1990s — mainly driven by women»

Increasing working hours among already fully employed people doesn't fix this. It worsens inequality and reduces opportunities for the underemployed or unemployed.

As Heiner Flassbeck emphasizes in a recent interview:

Prosperity is best defined as wages per hour. The only relevant question is: do we have a productivity per hour that provides this wage - plus profit for the companies. If this is the case, which is obvious for Germany, working more has nothing to do with prosperity.

If companies are profitable and productivity allows high wages already, there's no economic rationale for increasing hours - unless:

Wages are stagnating and employers want more output without increasing headcount.

The policy is ideologically driven (e.g., austerity, competitiveness narratives).

There's a push to shift bargaining power away from labor.

Historically, working time reduction has gone hand-in-hand with progress. From the 12-hour days of the Industrial Revolution to the 8-hour day and 35-hour week in Germany, each step was an achievement of civilization enabled by gains in productivity.

In fact, many post-Keynesian and ecological economists argue for shorter work weeks to:

Improve labor market inclusion.

Enhance well-being.

Distribute work more fairly.

Reduce environmental impacts.

The call for longer hours seems economically incoherent in the German context. It may reflect political pressure, cultural beliefs about "hard work," or business interests—but not sound macroeconomic reasoning.

If Germany can produce a high GDP per hour worked, the policy focus should be:

Fairer distribution of work and income.

Improved job quality.

Greater inclusion of the underemployed.

Support for work-life balance and sustainability.

Every society is free to choose the work-life balance. However, trying to tackle unemployment by reducing working hours regularly backfires because it creates a new demand problem.

As Heiner Flassbeck notes:

If wages fall or rise less, there is always a demand problem, because the increase in productivity, which makes the reduction in working hours possible in the first place, actually requires an increase in demand. After all, there are now more products available. If these are not in demand, unemployment arises and the reduction in working hours fizzles out.

There is no reduction in working hours with full wage compensation.