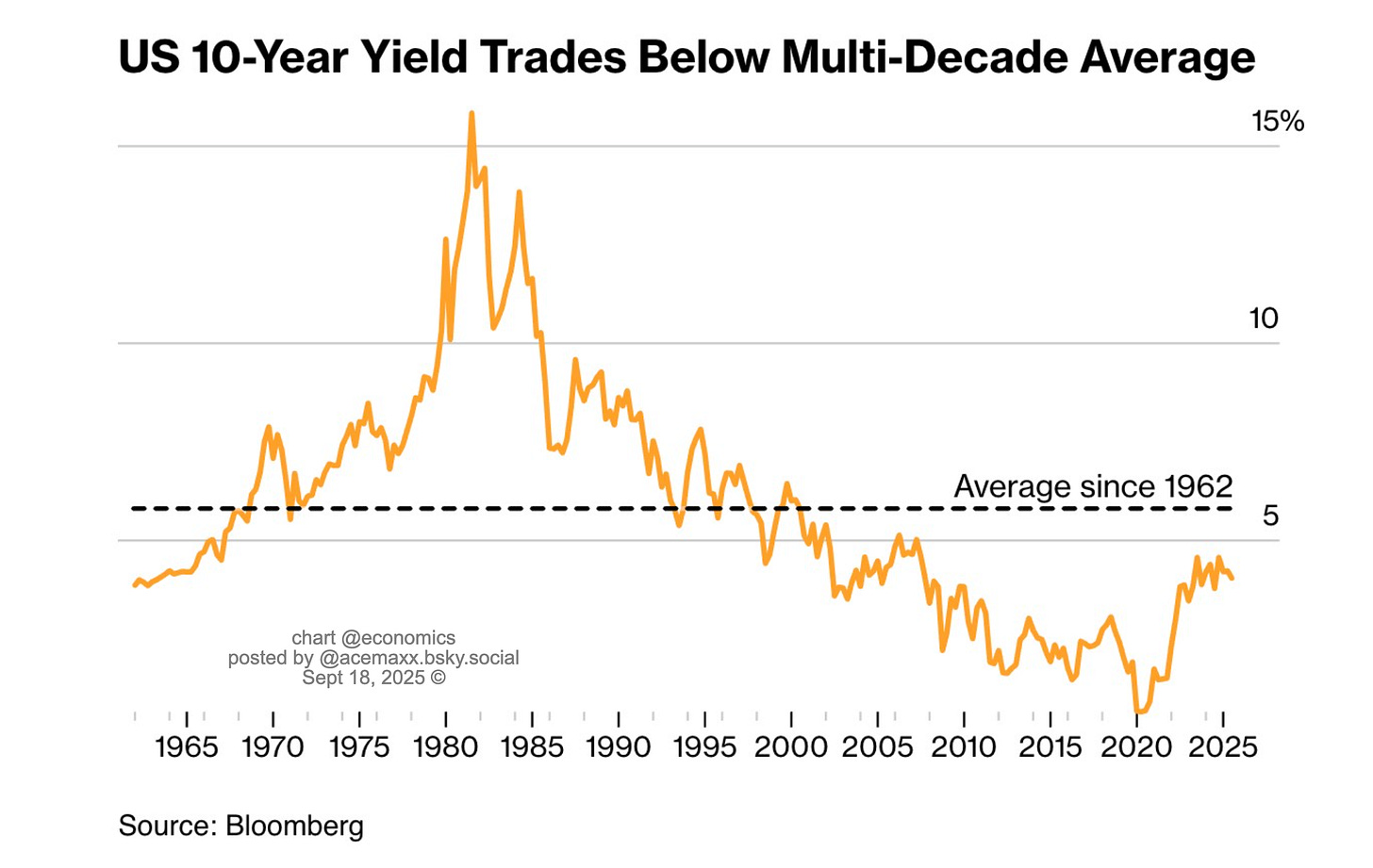

What Stephen Miran, US President Trump’s latest pick for Fed governor, is floating here — elevating “moderate long-term interest rates” to the level of an official mandate — would indeed mark a major shift in how the Fed operates.

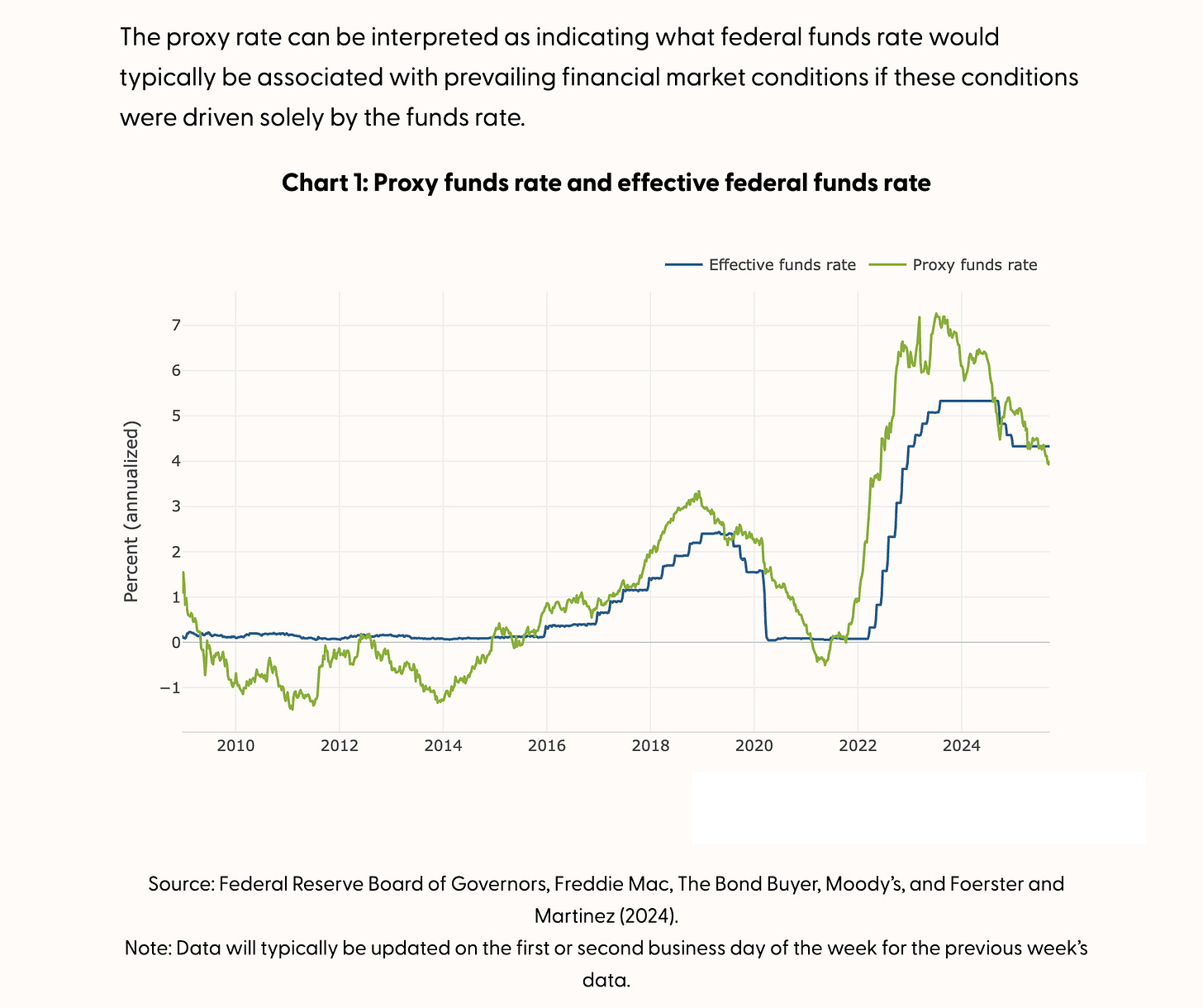

Fed already implicitly targets long rates

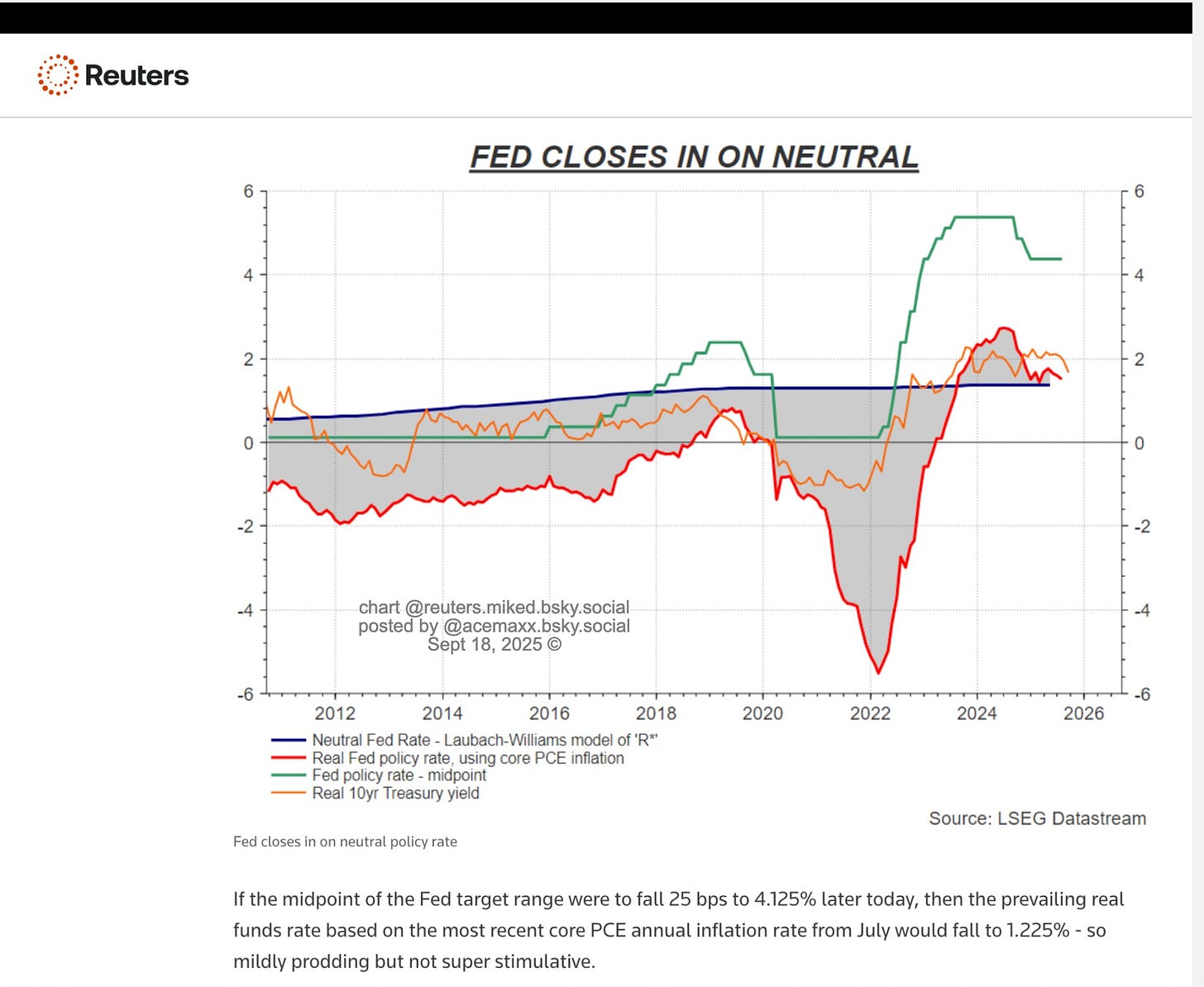

The Fed’s short-term policy rate anchors the yield curve; long rates are a combination of expected short rates + term premium.

When needed (e.g. QE, Operation Twist in the early 1960s), the Fed has intervened in long bonds. But these are tools, not mandates.

Turning “moderate long-term rates” into a mandate risks duplicating what is already baked into the existing framework.

Threat to Fed independence

The dual mandate (price stability + employment) is deliberately macroeconomic and broad.

Making long rates a formal target opens the door to political pressure: presidents or Congress pushing the Fed to keep borrowing costs low to finance deficits.

Potential conflict with inflation control

Suppose inflation flares up and the Fed must raise short rates aggressively. Long-term yields would normally rise as well.

But if the Fed is bound by a “moderate long rates” mandate, it might be pressured to cap yields (financial repression).

That would undermine inflation-fighting credibility, risking higher inflation expectations and volatility.

Historical caution: Yield curve control (YCC)

The U.S. actually tried this during and after WWII: the Fed capped long Treasury yields to keep government borrowing cheap.

Result: inflation surged in the late 1940s, and the Fed–Treasury Accord of 1951 had to restore Fed independence.

A “third mandate” would be a step back toward that failed experiment.

Market distortion and bubbles

Artificially holding down long rates risks fueling asset price bubbles (real estate, equities, credit).

Investors might be pushed into riskier assets (“hunt for yield”), increasing systemic vulnerabilities.

Legal and practical vagueness

The term “moderate” is ill-defined. Does it mean 2%, 3%, 4%?

Bond yields reflect global forces (foreign demand, demographics, safe-haven flows) beyond the Fed’s control.

Mandating moderation would invite constant disputes over what is “appropriate.”

Bottom Line:

While superficially appealing (who doesn’t like “moderate” rates?), a third mandate risks eroding Fed independence, conflicting with inflation control, repeating past mistakes, and distorting markets.

The Fed already has the tools to influence long-term yields when needed — but making it a permanent mandate would politicize monetary policy and potentially destabilize the system.

Note: To the surprise of many, it turns out that Miran was simply quoting a long-forgotten part of the Fed’s statute in full. Here is the link to the document: